Cover Design By Jennifer Merrick.

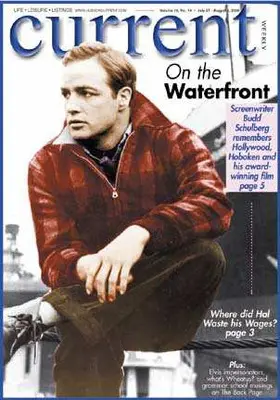

Decades have passed since longshoremen lined the docks of Hoboken, pigeon coops trimmed the tenement rooftops and Marlon Brando uttered those oft-quoted words “I coulda been a contender,” yet On the Waterfront, which was filmed entirely in the mile-square city, still resonates with audiences everywhere, thanks in no small part to Budd Schulberg’s award-winning screenplay.Decades have passed since longshoremen lined the docks of Hoboken, pigeon coops trimmed the tenement rooftops and Marlon Brando uttered those oft-quoted words “I coulda been a contender,” yet On the Waterfront, which was filmed entirely in the mile-square city, still resonates with audiences everywhere, thanks in no small part to Budd Schulberg’s award-winning screenplay. Last week, I phoned Schulberg, who is currently on holiday in Martha’s Vineyard. The 87-year-old author was kind enough to forgo an hour of his vacation to discuss Hollywood, Hoboken and his award-winning film. There has been controversy over the original inspiration for On the Waterfront, the story of Terry Malloy, a boxer and longshoreman who testifies against crooked labor leaders. The now-deceased Hoboken resident Anthony “Tony Mike” DeVincenzo, also a boxer and longshoreman who testified against crooked labor leaders, claimed that the Terry Malloy character was based on his life. DeVincenzo, who also raised pigeons like Terry Malloy, even went so far as to sue Columbia Pictures for $1 million, asserting that the movie studio responsible for distributing the film had invaded his right to privacy. A judge eventually ruled in Tony Mike’s favor and he was awarded $22,000. Other sources, however, reported that the movie was inspired by a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning magazine articles written by New York Sun reporter Malcolm Johnson in 1948. With delicate diplomacy, Schulberg addressed the debate last week. “There were some similarities, and Tony Mike’s life did overlap with the story and character I had written,” said Schulberg. “No one wanted to be contentious, so the studio settled with [Tony Mike]. But Johnson’s articles really triggered my interest in the whole project.” Schulberg, who was already the author of three successful novels, spent the next year of his life investigating waterfront corruption. “It was really more than research,” said Schulberg. “I became involved with the movement on the waterfront.” Schulberg said he was particularly fascinated with the waterfront priest Rev. John Corridan, whose life and struggles not only served as model for the Father Barry character in the film, but also inspired Schulberg to author a series of articles that were published in the New York Times and the Saturday Evening Post. At the same time, the acclaimed director Elia Kazan was working on his own tale of waterfront corruption with the playwright Arthur Miller. When Miller backed out of the project, Kazan approached Schulberg and the two men collaborated in Hoboken to make On the Waterfront “We thought Hoboken was the ideal setting for the movie,” said Schulberg. “It is self-contained, and we liked the look of the town: the harbor setting, the streets lined with bars, the rooftops. And the city officials were very supportive. It was a very hairy situation back then and fairly dramatic on the pier. The racketeers were along the shores and there was some feeling of threat. The chief of police even assigned a team to protect us. But we didn’t build a single set. It was all shot in Hoboken.” On the Waterfront’s location is a source of much pride for Hoboken residents who consider the setting an integral part of the film’s success. And while Brando, Kazan and Schulberg receive most of the credit, an article that appeared in Time magazine at the time of the film’s release also acknowledged the mile-square-city as the film’s silent star. “Seldom has the brick implacability of a workingman’s neighborhood stood staring in such an honest light – the tenement phalanx, the sad little parks, the ugly churches,” the article read. Budd Schulberg was born in 1914 in Hollywood, CA. The son of B. P. Schulberg, a pioneer film producer who received the first Oscar for his film Wings and ran Paramount’s West Coast studios from 1928 to 1932, Schulberg was raised on a diet of Hollywood dogma. With a movie mogul for a dad, he had his pick of Hollywood professions: he could have been an actor, a director, or a producer. But instead he decided to write. “In those days, I stammered very badly,” explained Schulberg. “I found writing was very helpful. And by the time I was in high school, I already thought of myself as a writer; an aspiring writer, but a writer.” Before he was 30, Schulberg was exposed to the dark side of Hollywood. His controversial novel What Makes Sammy Run, the story of a ruthless and conniving man willing to do anything to make it in Hollywood, was seen as a bitter indictment of the film industry. “The Hollywood moguls were very opposed to the book,” said Schulberg. Frustrated by the experience, he left Los Angeles for more tolerant pastures and moved to a farm in Bucks County, PA before finally settling in Long Island, where he has lived for the past 30 years. “When Kazan first approached me about making On The Waterfront, I told him that I didn’t like Hollywood,” said Schulberg. “I didn’t like the way that writers were treated. And Kazan told me, ‘If you do this project, I’ll respect the screenplay. I won’t change anything without your approval. You’ll have the final word.’ Until Kazan came to me that day, I thought I had left Hollywood behind.” Not quite 40 years old, but already a veteran of the Hollywood studio system, Schulberg was not surprised when he and Kazan had trouble making the movie. Several Hollywood studios passed on the project, and Schulberg had doubts whether the film would ever get made. Of course, the obstacles only made the film’s success that much more satisfying. After topping box office sales and receiving much critical acclaim, in 1955 On the Waterfront won eight Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actress, Best Editing, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction and Best Story and Screenplay. “Marlon Brando thought the concept of awards was kind of tacky, and he was very vocal about it, so the columnists started to come down on him,” Schulberg said. “Kazan and I thought, after everything we had suffered through trying to make the picture, it would be nice revenge if we won the awards. So I went out with Brando and had a talk with him. He’s a very changeable individual, and he also appreciates the underdog. So I told him that writers in Hollywood are underdogs, the picture itself is an underdog and the longshoremen are underdogs. This is an underdog project. And that got to him. He cooperated after that. He got all dressed up and came with me to the Foreign Correspondents Awards and behaved very well. And that helped the film win.” Of course, it’s hard to imagine what On the Waterfront would have been without the young and exceptionally fit Brando, with his signature slow speech and soulful eyes, portraying Terry Malloy. But legend has it that Brando originally vetoed the project and for a while it looked as though Hoboken’s native son, Frank Sinatra, would be the performer to bring Terry Malloy to life. And then, as temperamental artists are prone to do, Brando changed his mind. “Frank was really mad, and with good reason,” said Schulberg, judiciously adding, “I don’t think anyone has that magic that Brando has. He brings that little extra to each role. But Frank Sinatra is an excellent actor, and I still think it would have been a very good movie and very effective with him as Terry Malloy.” Contemporaneous with the making of On the Waterfront, a group of French filmmakers led by Francois Truffaut developed auteur theory. Designed to defend the Hollywood studio film, auteur theory identifies the director, not the screenwriter, as the author of a film. As someone who has dedicated his life to the written word, Schulberg has obvious problems with the ideology. “I hate auteur theory,” he said emphatically. “I think the auteur concept is a way of depriving the writer of his rightful identity and his whole proprietary relationship to the film. It’s outrageous to call it a ‘so and so’ film, referring to the director. Auteur theory is a huge vacuum cleaner that sucks up all of the credit to the director.” A member of the Writers Guild of America, Schulberg has spent 50 years of his life fighting for the prerogatives of writers. “I watch the Awards shows year after year and I have noticed a trend,” he said. “When Gwyneth Paltrow won for Shakespeare In Love, she thanked the producer and her agents. She thanked her hairdresser and every member of her family. She must have thanked 50 people. But she never mentioned the writer. She didn’t even mention Shakespeare. They don’t want to thank the people who created their characters and who put the words in their mouth. There can’t be anything without the writer. As you can see, I feel very strongly about this.” Over 50 years have passed since Schulberg left Hollywood behind, but the 87-year-old author can still stir up his fair share of swells. Ben Stiller has recently expressed interest in making a movie version of What Makes Sammy Run, the very book that tarnished Schulberg’s view of the town. With prudence acquired over years in the business, Schulberg’s optimism was tempered with understandable caution. “It would be great to see What Makes Sammy Run made into a film,” he said. “But I’ve seen so many Hollywood projects fall through that I don’t expect much.” On the Waterfront, live The City of Hoboken is presenting a theatrical staged reading of On The Waterfront on Thursday, August 3 at 7 p.m. at the Frank Sinatra Park Amphitheater (Frank Sinatra Drive between Fourth and Fifth streets). Directed by Kelly Patton, the production will feature members from the original Renegade Theater/Off Broadway production, including Kevin Breslin as Terry Malloy, Vincent Pastore as Charlie Malloy and Charles Rucker as Father Pete. Following the reading will be a discussion panel with Budd Schulberg, Kelly Patton, President of the Hoboken Historical Museum Lenny Luizzi, Hoboken Director of Cultural Affairs Geri Fallo and Tom Hanley, an actor from the original movie. The production is free. For more information call 420-2207.

Our Digital Archive from 2000 – 2016