Second in a three-part series

Editor’s Note: This story is the second in a three-part series that looks at the time in the 1930s and 1940s when shacks were replaced by federal low-income housing in North Bergen. A box of photos and historical documents pertaining to the time was found recently in a North Bergen Housing Authority office.

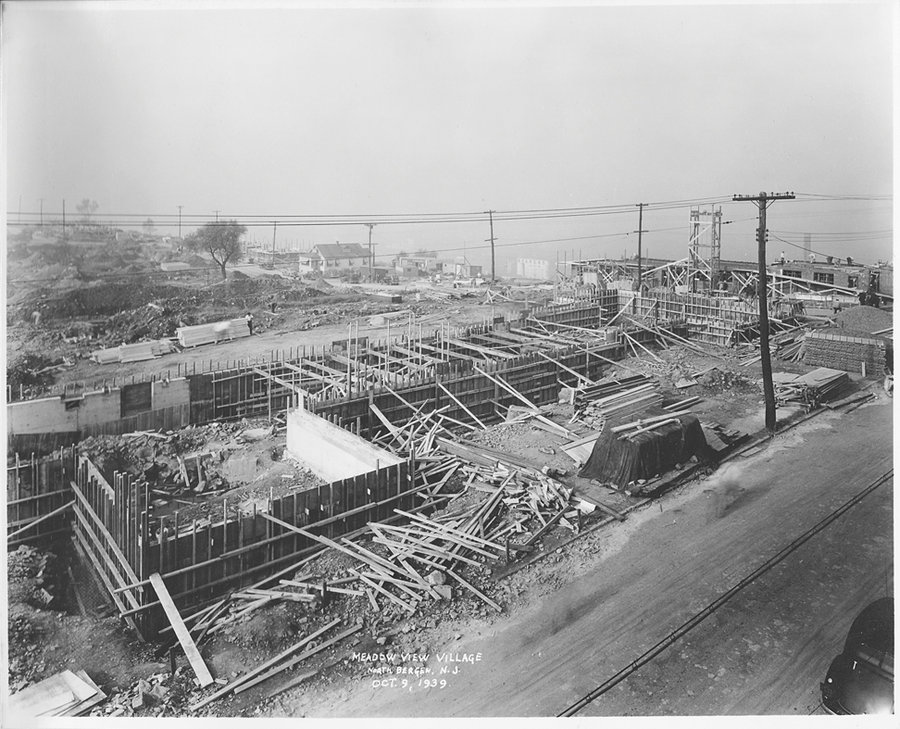

New Jersey Gov. A. Harry Moore proudly presided over the dedication of Meadow View Village on Oct. 14, 1940, from atop a specially erected 100-foot platform in front of 2,500 spectators.

Calling the new federal low-income housing complex in North Bergen “a monument to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the great humanitarian,” Moore was quick to take credit for an amendment requiring a playground in each federal housing project. Roosevelt had enacted the United States Housing Act of 1937 that allowed North Bergen and other communities to fund such affordable housing projects.

Meadow View Village cost in the neighborhood of a million dollars to build, at a time when the country was just emerging from the Depression. The opening was delayed several times and the project generated controversy almost from its inception.

Last year, Gerald Sanzari assumed the role of executive director of the North Bergen Housing Authority and found documents pertaining to the new complex in a closet.

“A lot of people don’t realize how much history there is here,” said Sanzari, “when you think about how many generations have come through these buildings.”

Shacks

In the 1930s, the township condemned or purchased the dilapidated shacks in the area and razed them in 1939 to make way for eight new buildings containing 172 apartments.

This was just two years after the Lincoln Tunnel first opened, and the same year Route 495 was extended west through North Bergen to Route 3.

“A lot of people don’t realize how much history there is here, when you think about how many generations have come through these buildings.” –Gerald Sanzari

____________

War clouds were darkening the skies overseas, but at home things were looking rosier. For the moment.

1,000 applications for 172 apartments

Thursday, Oct. 12, 1939 was the day residents were allowed to apply for housing in the new complex, still under construction. Eighty people showed up that day. Another 140 had somehow managed to get their applications in early.

By the end of the second day the town had received more than 300 applications for the 172 apartments.

Requirements were strict. “Families having a total income of more than $1,300 will not be eligible to apply,” wrote Housing Authority Chairman James T. Flannery in a statement issued in December 1939. “They must at present time be living in a sub-standard dwelling; preference will be given to families with children; it will be required that at least one adult member of each family must be a citizen; it will be required that applicants have lived in North Bergen for a period of one year or more; no cats or dogs will be allowed.”

Three-room apartments would cost $22 per month. Apartments of four and a half rooms would be $23 and five and a half rooms would go for $23.50. The projected completion date was March 1, 1940. This was pushed to April.

The first delay had been announced in January, amidst reports of faulty materials used in construction, forcing a 90-foot wall to be torn down and rebuilt. Flannery resigned as head of the housing authority almost simultaneously, claiming his decision had nothing to do with the controversy. He said his business as an importer and exporter was demanding too much of his time.

Then the opening was pushed to May. Officials cited additional delays because of cold weather, as well as extended time spent clearing the old slums, securing titles, and building on nearly solid rock.

By the time the completion date was delayed again to June, about 1,000 applications had already been received.

Open for business

The DellaDonna family was among the first 50 notified on June 1, 1940 that they had been accepted as tenants. Breadwinner George was a custodian for Public Service Gas and Electric Co., making $1,200 a year. He had four kids, ages 2 to 13, and all were overjoyed to learn the apartments would be ready for occupancy on July 1.

Anna Cooney, the widow of a veteran from The World War (there had only been one at this point) and one of the initial 50 selected, couldn’t be bothered by waiting. According to the Jersey Observer of June 29, 1940, “Yesterday morning, with most of the cement still soft and workmen bustling around, she informed the Housing Authority that she was moving in. Following a hurried consultation, Mayor Paul Cullum of North Bergen and several officials were rounded up, a car sent for Mrs. Cooney, and she was greeted at her new home as she and four of her five children alighted from the auto.”

By the time the buildings officially opened on July 1, most of the 50 families had already moved in. Eleven days later, the first baby was born to tenants of the new village: Joan Knapp, child of Howard Knapp, a counterman at the 57th St. Diner on Hudson Boulevard. (Decades later, the street would be renamed John F. Kennedy Boulevard.)

The dedication ceremony on Oct. 12 featured not only Gov. Moore’s speech but a parade, brass band, countless other speakers, and a fireworks exhibition with a rocket dropping a parachute holding aloft an American flag, which drifted over the speakers’ platform, much to the delight of all.

The war years

“Houses vermin infested,” screamed the headline of the Jersey Observer on Oct. 3, 1941. “Tenants must vacate for fumigation.” All 172 families were required to dismantle their beds, remove all food from the premises, and leave their dwellings for 28-hour periods while “deadly hydrocyanic gas” was used to fumigate the units.

Authorities claimed the fumigation was routine, a formality that should have been completely shortly after opening but delayed because funding wasn’t available at the time.

But as it turned out, it wasn’t the vermin who were the real health problem in the development.

Within a month, on Oct. 21, the Hudson Dispatch reported the third case of “infantile paralysis” (polio) in North Bergen: a 6-year-old resident of Meadow View. The family was quarantined, the playground closed “as a precautionary measure,” and families were urged to keep children apart.

Barely six weeks later the country would find itself at war after Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941.

The following month, a revised rent schedule was adopted at Meadow View Village, “commensurate with rising incomes of some tenants.”

“With the general improvement in business conditions, brought about by the defense effort, a number of families in the development have an income higher than the statutory maximum permitted for tenancy there under the old schedule,” said new Housing Authority Chairman John J. Roe.

At the request of the U.S. Housing Authority, the upper income limit was abolished, with sliding scale rents implemented, meaning some rents increased and others decreased to a minimum of $17 per month for families of two making up to $800 a year. “The schedule will be effective during the present war emergency,” said Roe.

Sixteen residents of Meadow View Village enlisted during the first year of the war. By June of 1943 that number was 37, including one who went missing in North Africa and the six Dundas brothers, all of them graduates of Horace Mann School and Union Hill High School. (One, Peter Dundas, age 22, did not make it home. When his ship was torpedoed off Tunisia, he escaped on a lifeboat but later drowned when the vessel capsized in stormy seas.)

The war in North Bergen

As the war overseas approached its end, domestic battles began to escalate. “Meadowview Village called unclean and rat-ridden,” announced the Hudson Dispatch of Feb. 27, 1945, quoting from a meeting the night before of the Westside Democratic Club of North Bergen. (Amidst the conservation efforts during the war, the name of “Meadowview Village” had contracted from three words to two.)

“Some members, who said they were residents of the housing project, said the ‘village’ was overrun with rats; that the houses were not kept clean, and children were denied the use of the playground there,” read the article, which also pointed out that the Westside Democratic Club was “believed to be under sponsorship of Traffic Court Judge James O. Chasmar who is opposed to Mayor Cullum.”

In a scenario played out endlessly in political arenas worldwide, the two sides hunkered down for a war fought with insults and accusations.

A reporter for the Hudson Dispatch subsequently interviewed numerous tenants, finding most denied the charges of “filth” at the village, including one who “denounced the charges made by the club, declaring that the club is trying to create a political issue against the township officials.”

Chasmar and the Westside Democratic Club continued to slam the mayor for mismanagement, going so far as to charge that the administration was using intimidation to try “to put the ‘quietus’ on the recent uprising.”

“[Chasmar] said that many of the residents have been approached by representatives of the local administration who ‘used Gestapo methods to keep the tenants from speaking freely,’” wrote the Jersey Observer on June 27, 1945, mere months after Hitler’s forces were defeated in Europe. “Judge Chasmar announced that he has learned of threats of eviction being used as one of the main weapons to keep the situation under wraps.”

End of an era

By 1947 the fighting had ended, both overseas and in North Bergen. An era had passed. The “present war emergency” was over, and it was time for a change.

“[Sixty] out of 172 families residing in the Meadowview Village project in North Bergen are to receive notices today that their incomes make them ineligible to remain as tenants in the settlement,” wrote the Jersey Observer on May 24, 1947.

Eviction notices were issued beginning in July, with families given six months before court action would be taken.

The mandatory edict was dictated by the Federal Public Housing Authority in all low-income housing projects across the country so that “low rent apartment may be returned to those in the low income sphere,” according to FPHA Chairman Carmen LaCarrubba.

The nation had entered the post-war years. A boom was on the horizon. Change was in the air. The initial generation of Meadow View (two words) tenants had reached its end.

Read the final installment in this series, featuring recollections from one of the first tenants of Meadow View Village, in next week’s North Bergen Reporter.

Art Schwartz may be reached at arts@hudsonreporter.com.