When David Mearns was a youngster growing up in Weehawken, he was always fascinated by water. "I was always keen about fishing, even when I was a little boy," Mearns said in a phone interview from his home in London last week. "I used to go fishing down by the water of the Hudson River. My mother grew up in Pennsylvania and when I would go there, I would go fishing with my uncles. Because of that, I always knew that I was interested in an outdoor career. So I did research, got career books, to see where I could go. I had to do something with fishing, so I figured I would study marine biology."

Upon graduating from Weehawken High School in 1976, Mearns headed to Fairleigh Dickinson University to major in marine biology. He graduated in 1980 after studying in St. Croix in the Virgin Islands for a semester, then headed to graduate school at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

"When I went to grad school, the focus became more on marine geology," Mearns said. "During that time, I started to study the sedimentary process of finding things on the sea bed, using sonar equipment and maps of the seabed. I learned how to find shipwrecks and air crafts that had settled to the seabed. I became very interested in the technology involved. I was able to become proficient using the instruments, not just the science involved."

This began a career for Mearns in search and recovery missions along the ocean’s floors.

Recently, Mearns enjoyed his finest moment, finding and locating the wreck of the HMS Hood, a historic British battleship that was sunk in a battle with the German battleship Bismarck some 60 years ago in the Denmark Strait off Iceland on May 24, 1941.

More than 3,500 sailors perished in the sinking of both ships – 1,415 sailors and crew aboard the Hood and 2,131 people aboard the Bismarck. It was the single largest loss of life in British Royal Navy history. Only three British sailors survived the devastation to the Hood.

Mearns became interested in finding the Hood, but didn’t know the importance it had to the British public.

"I had to get support from the British Naval Association, but we also needed to get a sponsor to fund us," he said.

BBC-TV’s Channel 4 became the sponsor to fund the project to find the remains of the Hood.

"The Bismarck had already been found and that story had been told," Mearns said. "But we needed to locate the Hood and tell her history. The Hood had the same glorious life that the Bismarck had. For 20 years, the Hood stood as a symbol of supremacy and sea power. To have both lost in one dramatic battle was amazing. They were both beautiful ships. It’s difficult to say that about war ships."

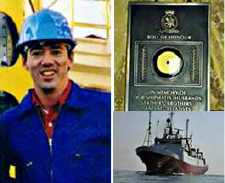

After receiving the sponsorship from the British television station, Mearns assembled a crew, using the most advanced equipment available and the ship MV Northern Horizon used by Dr. Bob Ballard to discover the remains of the Titanic. A side scan sonar, called the Ocean Explorer, was sent from the Horizon to the sea bottom in search of the remains.

It was a tedious process that took much patience because no one knew the exact location of the Hood, some two miles below sea level.

Once the Ocean Explorer finds something that could resemble ship remains, then the Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) is lowered to the seabed. Built to withstand the tremendous pressure that the depths of the ocean produce, the ROV can motor along the seabed, complete with lights and cameras, to videotape and photograph the findings.

The ROV is operated by staff aboard the Horizon, much like the way a person would use a joystick in a video game.

The lights and the cameras used to shoot the wreckage were also top-notch, in order to secure the images for the course of history. Most deep-sea footage gives off a bluish tint that is hard to decipher when broadcasted.

"We were also able to transmit the images back to the mainland almost instantly," said Mearns, who led the recovery expedition. "From 3,000 meters below the surface, that was outstanding."

The Horizon set its location some 250 miles west of Reykjavik, Iceland.

After doing research in finding its location for six years, then actually surveying the area from last February, the crew finally located the remains of the Hood on July 23.

"Seeing her for the first time really gave me mixed emotions," Mearns said. "Once we knew we found her, there was a sense of euphoria, knowing you were the first to find her. That was exciting, the culmination of a lot of work. But immediately, you saw the condition of the middle section of the Hood and it was overturned. It was heartbreaking. The damage was far worse than any of us expected. It was a shock to see her in such terrible condition. So the feelings were bittersweet."

Mearns added, "But the whole reason for doing it was to be able to tell the story the right way, through the eyes of the men who survived it, to tell their gripping accounts, then combine them with the images we found. It is interesting to everyone, an important part of history."

The remaining survivor, Ted Briggs, who is now 78 years old, contributed a plaque in memory of the sailors who perished. Mearns’ crew was able to place the plaque on the seabed, near the remains of the Hood.

Mearns was also able to produce a documentary on the expedition, which aired recently on PBS in America and will be shown again on dates to be determined. Mearns has also written a book about his experiences in locating the Hood.

"It’s important for the next generation to know the story," Mearns said. "It was important to properly recognize the sacrifice that these men made, and to place that memorial plaque on the seabed meant so much to all of us."

Mearns has enjoyed an interesting career of finding lost vessels. His first job was with Eastport in Maryland, which used to recover lost torpedoes and ships. Eastport was the company that helped to find the remains of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1990.

He then helped to locate a bulk carrier ship, Derbyshire, from England, that sunk during a typhoon near Japan in 1980, with 44 people on board. The vessel was the largest single maritime loss in British history and Derbyshire was located in 1994, to help the shipping industry prevent similar tragedies.

Mearns’ recovery of Derbyshire led to the Hood project.

Although Mearns has no idea what project he may tackle next, he will remain in London, which has been his home for the last six years since he started the Hood project.

"But I’m always happy to hear from home," said Mearns, whose mother, Caroline, and sister, Susan, still reside in Weehawken. "I haven’t forgotten Weehawken. I may live in England, but I’m still a Jersey boy."

"I’ve been really fortunate to work on such high profile and significant projects," Mearns said. "But working on this project, with the historical significance of the Hood and Bismarck, is a crowning achievement."

For more information about Mearns’ journey and the discovery of the HMS Hood, log on to www.channel4.com/hood.