The Fund for a Better Waterfront (FBW) recently celebrated the 25th anniversary of the narrow legal victory that led to the group’s birth. After a July 1990 city referendum halted a Port Authority plan to build a 33-story office tower on Pier A, the vote’s organizers sat down to create an alternative vision for the waterfront.

That proposal by the waterfront group called for a continuous public park along the entire eastern edge of Hoboken. It served as the basis for the 1995 city plan that created Pier A and Pier C Park and the promenade that connects them.

For many long-time activists, last month’s anniversary celebration was tempered by victories not yet won and battles still to come. In December, the Hoboken City Council approved one of the largest redevelopment projects since the South Waterfront – a massive makeover of 36 acres of NJ Transit-owned rail yards south of Observer Highway – over the strong objections of FBW members.

For the last six months the group has once again developed an alternative plan, led by the same architect and urban planner who laid out their waterfront proposal a quarter century ago.

The FBW concept for the Hoboken Yards seeks to address the major problems it sees with the current proposal: a lack of meaningful open space, buildings that they believe don’t make sense, and a grid layout that they say will generate disastrous traffic.

Their alternative design will be a test of how much sway FBW still holds in Hoboken’s civic sphere. The state law that enabled the group to force local referendums in 1990 and 1992 has since been amended, stripping the most potent weapon from its arsenal.

And though many of the politicians now leading Hoboken’s city government are former development activists who see FBW as a forebear, changing the Hoboken Yards plan would force them to denounce their own creation.

That darn plat

According to Craig Whitaker, a New York-based architect and former NYU Wagner planning professor who advises FBW, the biggest issue with the current Hoboken Yards Redevelopment Plan is that it has no plat.

A plat is the basic blueprint of a city. It clearly delineates what space will be public and private, typically in the form of streets and lots. While the Hoboken Yards plan contains a number of “atmospheric” drawings suggesting what the development might look like, said Whitaker, it never specifies exactly where public streets will go within the project, and thus where future buildings will be.

“The only thing they’ve got in their minds is getting approval, so they can get going.”—Craig Whitaker

____________

This layout, along with a separate county-led redesign of Observer Highway that will reduce the road to one through-lane in each direction, will result in “a dramatic increase in traffic on Newark and First [streets], and maybe on Second,” predicted Whitaker.

In FBW’s plan, by contrast, all eight north-south streets from Adams to Washington would continue through the Hoboken Yards area. While construction on the “out of wack” Observer Highway redesign has already begun, Whitaker said increasing the number of streets feeding the rail yard service road would relieve much of the pressure the redesign creates, not to mention add roughly 120 new on-street parking spaces to the city.

The FBW plan has the added bonus of continuing the Hoboken street grid that was laid out by the city’s founder, Colonel John Stevens, in 1804. If Whitaker and FBW are to be believed, the very character of the city is derived from that layout.

Courtyards and corridors

Of course, re-creating the low-rise residential feel of Hoboken is about more than the size of each block. According to FBW, the buildings themselves must reflect the prevailing envelope of structures in Hoboken.

The group’s plan calls for the residential buildings in the Hoboken Yards to be a modified version of the iconic Hoboken donut block, with buildings starting close to the property line and private courtyards in the middle.

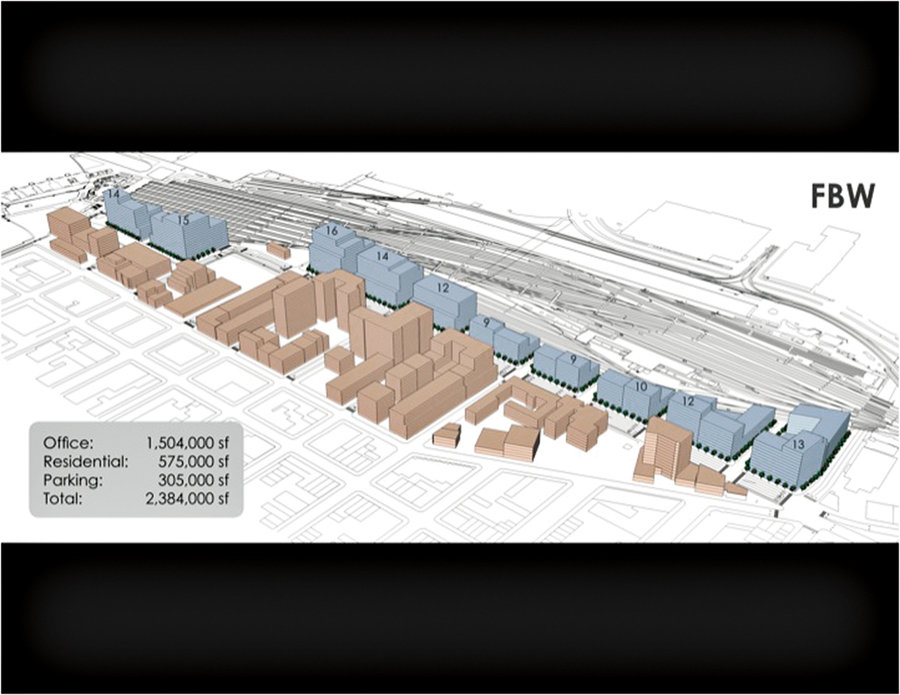

Overall, the FBW plan maintains the total floor area of 2.3 million square feet found in the city plan, but contains no buildings taller than 16 stories, while the city could allow commercial buildings as tall as 24 stories.

FBW achieves this primarily by doing away with the many setbacks in the city plan that pull buildings away from the street to allow “scenic easements and visual corridors,” in Whitaker’s words. This emphasis on setbacks creates structures that no developer in his right mind would want to build, according to him.

“What the developer wants is the most amount of rentable space he can get out of the project,” said Whitaker. “He can’t sell stairways, he can’t sell elevators, he can’t sell corridors.”

In mockups shared with FBW, LCOR attempts to follow the city’s instructions, with ground floor retail in every building and parking lots reaching nine stories high in some instances.

“The only thing they’ve got in their minds is getting approval so they can get going,” said Whitaker.

Finishing the waterfront

The final major concern of FBW is ensuring that the open space created by the plan be of maximum utility to the public. The City Council-approved plan mandates at least 4.5 acres of new open space, but it comes in the form of pocket parks and piazzas tucked around the edges of the project.

Whitaker said these “parkinas” are rarely used in practice, since they are too small for activities and are assumed to be private because they abut private buildings. Their presence in the city plan “betokens the fact that nobody has taken this very seriously, and nobody with any development experience,” he added.

FBW’s preferred alternative would be to create the same amount of open space or more in a single consolidated unit where it would be of the most use, on the Hoboken waterfront.

It is FBW’s most ardent desire to finish the public waterfront concept it first proposed after the 1990 referendum. The biggest remaining step is purchasing Union Dry Dock on the central waterfront, the last fully functioning vestige of Hoboken’s former shipping industry.

Whitaker estimated the cost of buying and renovating the dock at around $27 million. Though that seems high, he said the cost of building a performing arts center, which the city of Hoboken has stated may be a demand in its negotiations with NJ Transit, could run between $23 and 30 million depending on its size. If the arts center and pocket parks were abandoned, Whitaker believed NJ Transit could easily afford to turn Union Dry Dock into a park.

Still hope

If anything should give FBW hope that their concept could still be adopted via amendments to the Hoboken Yards plan, it is the glacial pace at which negotiations between the city, NJ Transit, and LCOR are unfolding.

As of May, official negotiations over a redevelopment agreement had yet to begin, according to city spokesman Juan Melli (the city did not respond to more recent questions about the status of negotiations).

“The next major step in the process is conducting a traffic analysis of southern Hoboken,” said Melli. “In order to do so, we are waiting for NJ Transit and their contract developer to submit a pre-submission form to enter into negotiations with the city so that they can fund the traffic analysis.”

If the current plan will generate traffic as bad as FBW says, it will ostensibly be revealed by this traffic analysis. According to FBW Executive Director Ron Hine, LCOR indicated openness to the group’s plat design in discussions.

“They initially said that they started out with something that resembled more or less what we’re proposing,” said Hine.

The harder step will be convincing the mayor and City Council that the plan they shepherded into existence is flawed. Last week, City Council President Ravi Bhalla said that the city had met with FBW multiple times, and that he felt their concerns had been addressed.

“The current plan…was the result of years of careful planning that included an extensive public process,” said Bhalla. “FBW, together with many other interested citizens and organizations, actively participated in the process, and many ideas suggested by the public, including FBW, were incorporated into the plan.”

In response to questions from The Hoboken Reporter, an NJ Transit spokesperson declined to comment specifically on the FBW plan.

“NJ TRANSIT continues to work with its developer, LCOR, and the city of Hoboken to advance a redevelopment plan which is in the best interest of NJ TRANSIT, meets the transportation needs of our customers, and is consistent with Hoboken’s Redevelopment Plan,” said the spokesperson.

Carlo Davis may be reached at cdavis@hudsonreporter.com.