Muhammad Ali’s passing last week at the age of 73 wasn’t totally shocking. After all, the most recognizable sports personality of the 20th century was in severe decline over the last 30 years, with Parkinson’s disease taking away a lot of his motor skills and his ability to talk, which was perhaps his most lethal weapon.

But the three-time world heavyweight boxing champion was more than a sports icon. He was a world figure, a man much larger than the image he portrayed in and even out of the ring.

Incredibly, this is a man who transformed himself from being an absolute hated villain, a draft-dodger who was banished from our great nation because of his refusal to report to his local military headquarters, a loud-mouth from the South who was so reviled even by his own race for his treatment towards other African-American boxers, to a sympathetic beloved soul who everyone just wanted to reach out and hug to stop him from shaking.

How many other figures in American history could lay claim to that, going from hated creature to beloved man in the matter of a few years? Such a transformation only takes place in professional wrestling.

In my lifetime, there has never been a figure like the man who was born as Cassius Marcellus Clay and turned into Muhammad Ali in 1965 after discovering the Islamic faith. In the 1970s, he was bigger than Richard Nixon, Secretariat, and Joe Namath – combined. He was more of a headline grabber than Watergate and Anwar Sadat.

There was no denying the enormity of Muhammad Ali, through his trilogy of fights with fellow champion Joe Frazier, battles that took years off both men’s lives, proved by the fact that both are now gone before they reached the age of 75.

The last four rounds of the third Ali-Frazier fight, dubbed “The Thrilla in Manila,” are some of the most violent and graphically physical images in sports history. How either man survived such punishment is beyond me.

Those days were very memorable to me, because as a 10-year-old on March 8, 1971, I was fortunate enough to attend the first Ali-Frazier fight at Madison Square Garden with my father.

I never did find out how my father was able to secure two tickets to that fight, but I just remember him standing over me to make sure my homework was completed.

Then my Dad told me to get in the car and that we were going for a ride, but I wanted to be home in time to listen to the fight on the radio, never letting on that we were indeed going to the Garden until we drove through the Holland Tunnel.

It was the last big event my Dad and I went to together, because he died that December.

And my favorite, namely Frazier, won the fight after knocking down Ali with a thunderous left hook in the 15th and final round en route to a unanimous decision.

I remember spending $20 to watch the third Ali-Frazier fight via closed circuit at the Stanley Theater in Journal Square on Oct. 1, 1975. I was a 14-year-old freshman at St. Peter’s Prep now and went to see that fight alone at around 4 a.m. local time, getting on the Bergen Avenue bus to head to the square.

I was cheering wildly for my man Frazier, who was winning all the middle rounds left and right, but was beaten blind by Ali in the later rounds, so badly that his eyes were closed shut and couldn’t see, causing trainer Eddie Futch to stop the fight in the 14th round. I still believe to this day that if Frazier had been able to stand and see for that final round, he would have been the heavyweight champion. But it wasn’t meant to be.

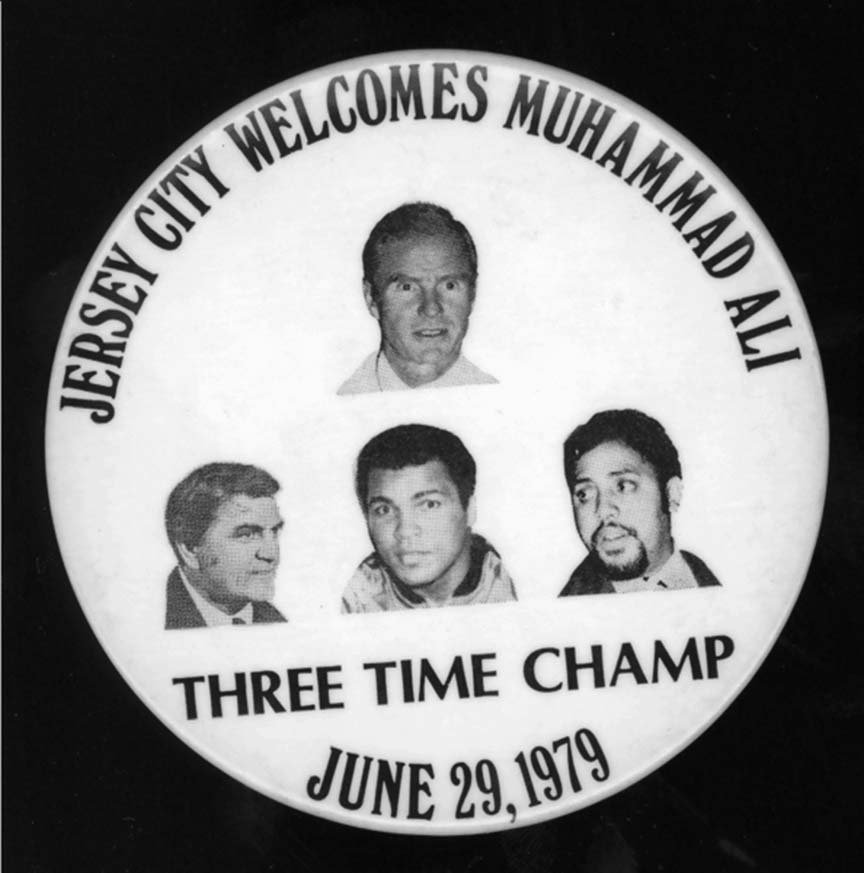

In 1979, Ali was in the midst of one of his several retirements from the ring when he agreed to take on then-Jersey City Mayor Thomas F.X. Smith in a charity boxing match at the Jersey City Armory in September of that year.

It was going to be for charity, but Smith, a former professional basketball player with the New York Knicks, took the fight somewhat seriously and started to rigorously train for the meeting with Ali.

Smith took to the streets of Jersey City, running with his dog, Henry Hudson, making like he was Rocky Balboa, without all the kids running behind him. Although in his late 50s at the time, Smith was determined not to allow Ali to make a spectacle of him by being in the best shape possible.

At that point, Ali was already a year out of the ring, a year after gaining revenge on Leon Spinks for taking away the heavyweight championship in February of 1978. Ali defeated Spinks in Sept. of 1978 to become the first three-time heavyweight champion, then retired from the sport.

So when Ali agreed to the meeting with Smith, he was retired for almost a full year.

In August of 1979, there was a breakfast held to promote the fight at the old Chateau Renaissance on Danforth Avenue, now a charter school. Ali was attending this breakfast just two blocks from my house, so how could I not go and try to get his autograph?

Sure enough, I was one of only a handful of people outside the building, awaiting Ali’s arrival. Sure, there were hundreds inside with paid tickets for the charity, but I was determined to meet him outside the catering hall.

When the limousine pulled up and Ali stepped outside, his handlers told people that he would not be able to sign autographs. However, Ali saw the small throng of people waiting, including myself, and reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out index cards.

Ali handed me a card that already had his autograph and he wrote quickly, “To James, best wishes,” to the “Muhammad Ali” that already appeared. The ink was the same. I think he thought there would be hundreds of people outside and he was going to have to sign each one. But there were maybe 10 people waiting, so Ali personalized my card.

That was my only encounter with Ali.

Turn the clock ahead 15 years and flash ahead to a fundraiser I was organizing to help defray the cost of heart surgery for a girl I once coached named Tracey Tullock.

It was a fundraiser at the Jersey City Moose Lodge on West Side Avenue and my good friend Willie Wolfe, God rest his wonderful soul, wanted to do whatever he could to help the cause, so he brought a ton of autographed memorabilia he had, including from the 1969 Mets and boxing gloves, to give to me to raffle off.

And on the morning of that fundraiser, Willie brought me another special guest. He brought Joe Frazier to the event.

“Smokin’ Joe” was an amazingly friendly man who signed autographs for hours and eventually was dancing, doing the Electric Slide with the girl of the hour, who survived the heart surgery and is now a wonderful mother.

So I briefly met Ali and I danced with Frazier, all within a few blocks of where I was raised. How great is that?

So that was my thoughts last week when Ali passed away. Both Ali and Frazier had a major impact on my young life, on my adolescence, and on my adulthood and both were merely a few blocks of each other, a few years apart.

Jim Hague can be reached at OGSMAR@aol.com. You can also read Jim’s blog at www.jimhaguesports.blogspot.com.