The long road to approval for a new master plan for the Meadowlands on March 5 by the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission has been filled with historic and symbolic moments. Each official involved might well take credit for turning the state’s vision away from developing the Meadowlands and toward preserving it.

In 1995, Captain Bill Sheehan helped set up HEART Corp., a volunteer environmental group dedicated to saving the river – which late evolved into his current role as the Hackensack Riverkeeper. Sheehan was among the earliest voices opposing the 1995 master plan that called for significant development. It was his and other environmental groups working with him that helped get the Hackensack River listed as one of the most endangered in the county – due to the pressure of development.

In 1997, then Secaucus Mayor Anthony Just bargained with Hartz Mountain Industries to purchase 200 acres in the Mill Creek section of Secaucus that had been slated for 2,000 townhouses. Just, in conjunction with the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, vowed to turn the land open for preservation rather than allow another housing development. Just led the passage of an open space ordinance that would continue purchasing parcels of land in Secaucus for preservation. Under this ordinance, Mayor Dennis Elwell has led the council to purchasing various parcels that will lead to establishing a nature center and park at Old Mill Point and a walking trail along the shore of the Hackensack from the northmost point of Secaucus to the southmost point.

In 2000, Rep. Steve Rothman gathered many of those most responsible for maintaining the Meadowlands into his office, and drew a line on a map saying he wanted to preserve everything within that boundary. In the years that followed, Rothman procured funding that started a campaign to purchased remaining parcels of wetlands from private owners. He had taken people such as Senator Jon Corzine on tours of the Meadowlands to win additional support, introducing a proposal earlier this year that would save what is left of the Meadowlands for a development into a park.

“History is being made today,” said Sheehan before the boat on Feb. 26, “and we’re the one’s making it. The days of filling wetlands are over. The marshes of the Meadowlands are finally recognized for the public trust resources that they have always been. And while some folks might congratulate me on winning a victory, I must confess that if today is in fact a victory, it is one that is shared by many thousands of people.”

New plan seeks to preserve wetlands, not fill them

The Hackensack Meadowlands District, as defined by Mary Anne Thiesing, a regional wetlands ecologist for the US Environmental Protection Agency, is a 32-square-mile acre covering portions of 14 municipalities in Bergen and Hudson Counties. Of the original 21,000 acres contained in the district, 17,000 were wetlands and water, containing a vast array of wildlife plant including a marsh plants, a hardwood forest and white-cedar woodlands.

From the moment Europeans set foot onto the New Jersey shore, the district became the target of logging, diking and draining. The land was farmed, filled and contaminated. Over several centuries, nearly half of the wetlands vanished.

The earliest road in the Meadowlands, according to Ralph W. Tiner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, were built by colonists skirting along the edges of the swamp. Eventually plank board roads crossed the swamps, and then railroads, paving the way for future development.

Until the 1960s, the Meadowlands contained two dozen trash dumps covering more than 2,500 acres. These leached contaminated water into the rivers, creeks and mud flats.

Thiesing described the Hackensack River as “an open sewer with debris, oil slicks and other pollutants choking life out of its water.”

By 1968, she said, the contamination problem had intensified with numerous underground dump fires filling the air with pungent smoke.

One of the most significant moments for saving the Meadowlands came with the state establishing the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission in 1969 and the federal government passing the Clean Water Act in 1972. There was a disparity between the NJMC’s mission – which was to clean up the trash, maintain orderly developmentand manage the wildlife – and the Clean Water Act, which said that there couldn’t be any development at all on the wetlands. That led to the development of what was called a “Special Area Management Plan” (SAMP).

This document – which took 10 years to write and was released in 1995 with the participation of federal and state agencies as well as environmental activists – was supposed to map out the future of the Meadowlands for the next several decades. But many groups such as the Riverkeeper were so appalled by the development proposed that they went to war against its approval.

Since 1995, these environmental activists waged a campaign that eventually destroyed any chance of SAMP being passed, winning important allies such as Rothman and Acting Governor Donald DeFrancesco.

Forging a new plan

NJMC began making moves to forge a new Master Plan. The March 5 plan, the first major revision to the original 1970 plan, is the primary planning document for the NJMC. It provides a policy framework to promote the careful balancing of environmental and economic development needs in the district.

“This master plan will serve as a blueprint for a re-greened Meadowlands and a revitalized urban landscape,” said Susan Bass Levin, commissioner of the Department of Community Affairs and NJMC chairperson.

The new plan outlined several new and important goals, including preservation of existing wetlands, open space and the historical heritage of the Meadowlands, development only in upland areas, and adherence to the state’s new anti-sprawl regulation by promoting redevelopment of brownfields. Redevelopment will be a key fact on this plan. The NJMC will focus on cleaning up existing brownfields on which hazardous materials, pollutants and other contaminants have been dumped.

The plan would seek better transportation modes, with an emphasis on mass transit and improvement of existing facilities. It would promote a balance of mixed housing types and open up the communication process to those communities affected.

“Most suitable land in the district has been developed,” the master plan concludes. “The majority of undeveloped areas remaining in the district are environmentally sensitive and unsuitable for development.”

Transportation

Transportation improvements in the new master plan include improvements in the area of the Secaucus Transfer Station to become a hub of transportation in the area and a possible tourist destination.

Under this plan, Route 1&9 in Jersey City, Paterson Plank Road in Secaucus and North Bergen and Meadowlands Parkway in Secaucus will be among the roads that receive priority for funding from the NJMC when repairs are needed.

Bus service will also be provided from the new Secaucus Transfer station, offering NJ Transit and shuttle service to Hudson County and local employment centers.

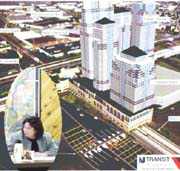

Secaucus 1st Ward Councilman Christopher Marra, who is a member of the stakeholder committee studying options for the hub, said, “They are looking at 680 acres [to rezone for a downtown transit village] in addition to the train station.”

Late last year, NJMC authorized NJ Transit to do a study for development around the train station to consider a village-like development for the area. Mayor Dennis Elwell said it could become a second downtown district for the town of Secaucus.