It has been almost two decades since Michael Rees began looking at how computers could impact his art.

“Right around the early ’90s, the intersection between the speed of the computer, graphics cards, and programs came together to make it possible to make something on the computer and get it out to the world,” said Rees.

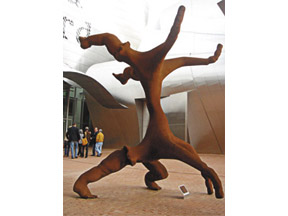

Rees’ sculpting starts with an idea. Then that idea is computed to an algorithm, or code, and entered into a computer. If it is one of his large-scale pieces, which are sometimes 18 feet high, it’s carved from blocks of wood, painted, and sanded to perfection. A plastic model of the same design can also be put into a machine that carves plastic with a laser, and a 12-inch model can be created in 12 hours.

He said he still remains suspicious of the technology he employs as a tool for his work.

“One of the reasons these technologies I use exist is because they are military industrial technologies,” said Rees. “They’re developed to make things, but things that kill people, so I think that one of the good things is as artists we balance some of that stuff by being creative instead of destructive.”

It’s important to remember that art stems from your consciousness and “heart,” said Rees.

Originally from Kansas City, Mo., Rees moved to North Bergen a few years ago after living in New York City and Germany.

He was the recipient of a 2007 New Jersey State Council on the Arts Individual State Fellowship Award, which enabled him to create “Converge: Gharib Bag,” a large-scale piece presently located at the Art Omi International Arts Center in Ghent, N.Y.

He will also be featured on NJN’s State of the Arts, which aired on Jan. 16 at 8:30 p.m., will encore on Jan. 21 at 11:30 p.m., and will afterwards be available online.

A child of the ’70s

Rees said that as a student at Vassar College, he found art and felt that suddenly possibilities opened up for him. He left college and signed up for art school, much to his parents’ chagrin.

“Slowly but surely, in that serendipitous way that magical things happen, I just started becoming a sculptor,” said Rees.

Rees said that the current state of the world, which is “falling apart,” makes him feel at home because it reminds him of that time in his youth when nothing was finite.

“I have a Facebook page like everybody else and … I wrote that I’m a child of the ’70s and I feel at home in broken first world institutions in stressed economic times, and it’s really true,” said Rees.

He said that the ’70s were an explosively creative time because the financial decline allowed people to focus their energy on different things. That time period embodied art as an alternative to the corporate machine, while Rees said that now sometimes art has become commercialized.

“[Now] we’re not on a super fast treadmill like we’ve been on for the last 10 years,” said Rees. “The money isn’t going to be there, so we’re going to have different motivations for doing things, and those motivations will be closer to your passions.”

Rees teaches sculpture and digital media at William Paterson University and said that his students, having the rug pulled out from under them, find the change in the times frightening. He said he doesn’t blame them.

Conflict creates art

Rees said that since he began sculpting in the 1980s, his art has always been a product of his current state of mind. He said he doubts he would have made the same pieces today if it were not for the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

Rees’ current sculptures are tree-like, with arms, legs, and other appendages in a constant battle. For him, they represent the battle between cultures, power, and his concerns. They make a statement on the dangers and benefits of artificial intelligence and life, all while being somewhat a product of that same technology.

“I think a lot of people look at my work and say ‘It ain’t right,’ ” said Rees. “In other words, a creature walking around like this, that is an amalgam of all these parts and pieces, uses, and ideas is a concept that makes people a little edgy.”

Instead of looking at another beautiful landscape painting, Rees wants someone’s brain to not be able to categorize his work. He feels the thought-provoking nature of his sculptures allows for him to connect to the world “mind to mind.”

Struggling with complexity

Rees said being a professor allows him to stay in touch and keeps his work from relying on what the market currently desires. He said that William Paterson University really upped the ante in his course and purchased expensive machinery. The Matrix Collaborative in Guttenberg has the same machinery that he, along with other artists, once had to pool their money together to purchase.

He now splits his time among his studio on Greenwich Avenue in New York City, the university, and being at home with his wife, a painter, Mary Ann Strandell.

One of his future goals is reinventing his studio practice so that it encompasses technology, machinery, and all of the social pressures of the world.

“You struggle with complex ideas and big things your whole life, and it takes a long time to get your arms around the complexities of your work, what drives you,” said Rees. “I think I’m well on my way.”