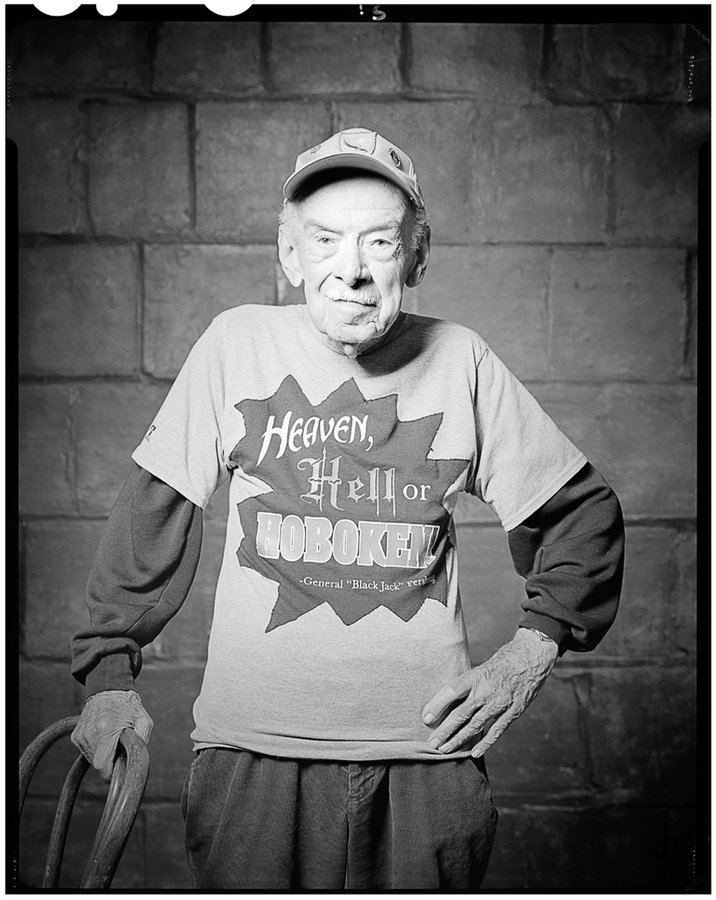

The town of Hoboken—and indeed our nation—should be honored to have World War II vets still among us. Craig Wallace Dale shot beautiful portraits of these American heroes, who took time out to share some of their memories from the war years.

Jack O’Brien, now 88, signed up when he was only 16 ½ years old. And, by the way, “signed up” is the right phrase. These young men were willing and able: Our ships were attacked at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and a genocidal maniac was murdering innocent civilians in Europe.

They heeded the call.

O’Brien was a steward on troop ships that crossed the North Atlantic some 17 times. He was in the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf. Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, the father of General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, commanded the camp in Basra. O’Brien was in England, Ireland, and East Africa.

As a steward, he says, “I fed the troops and was storekeeper.” On the ship John Erickson, which carried some 3,000 troops, a fellow sailor was actor Carroll O’Connor of Archie Bunker fame. “I never got to meet him,” O’Brien says. “If the Germans knew about him, they would have sunk that ship immediately.”

He says he was “surrounded by cruisers and destroyers firing off mines in the water.”

O’Brien was born and raised in Hoboken and still lives here. He says troops would leave from the docks in Hoboken, Baltimore, or Boston.

“I was very proud and very patriotic,” he says. Compared to today, “It was a different war, and a different life. It was our duty to go into service.”

He’s clear-eyed about our bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “It was them or us,” he says. “We didn’t start it. They bombed us. The Japanese caught us on a Sunday morning when half the sailors were in church.”

World War II soldiers had a perfect enemy in Hitler, who “was starving and burning people,” O’Brien says.

When the war was over, his ship transported precious cargo: war brides. “We carried hundreds of girls who married American troops in England and France,” O’Brien says.

But he waited until he got stateside to marry—a Jersey City girl.

O’Brien still participates in a fife-and-drum corps. He played at the World’s Fair in 1939 and continues to play throughout New Jersey.

O’Brien’s father, James J. O’Brien, was a World War I veteran, which is important, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the United States’ entry into World War I. The Hoboken Historical Museum is offering a lecture series that runs through May 7, 2017. Visit hobokenmuseum.org for details.

A lot has changed in Hoboken in the past century. “Rents went up, you know,” O’Brien jokes. No kidding. He says, “My mother paid $20 a month for our place on Monroe and Second.”

Two for the Price of One

Staff Sergeant Vincent Wassman was also deployed to a troop transport ship in the North Atlantic during World War II, ferrying soldiers to Europe and bringing the dead and wounded home. He trained at Fort Eustis in Virginia, serving from 1943 to 1945.

“We went back and forth quite a few times and ran into some hurricanes,” Wassman recalls. “It was a pretty big ship, with a thousand or so onboard.” Back then, ocean liners were used as wartime vessels. “When war came,” he says, “everything was turned over to the War Department.”

“It was the same as today,” he maintains. “Soldiers going off to war.”

After the war, Wassman came back to Hoboken and had a few peaceful years before he was drafted into the Korean War, in 1950.

He had an interesting experience at the Draft Board in Newark. “Who should walk in, straight from the Paramount Theater on 42nd Street and Broadway, but Sinatra,” he relates. “He was there the same day I was. He went to the front of the line, and everybody booed him—we were standing there in our BVDs [underwear]. He claimed he had a punctured eardrum, and they sent him back to the Paramount.”

Wassman, meanwhile, was shipped over to Japan and then to Korea.

Born and raised in Hoboken, Wassman still lives in the house on Bloomfield Street, where he and his wife, a nurse at the medical center, raised five kids.

He bought the house for $14,000. “It’s worth $2 million today,” he says.

“At that time, nobody wanted to live here,” he says, “and now you can’t afford it.

“There are so many old things to talk about,” he says. “They were innocent years, let’s put it that way. Everybody knew each other. You’d walk to the theater, and nobody would bother you. You’d stay out late and come home at one or two in the morning.

“Give me back the old days,” he says. “I’m an old-fashioned guy.”

Wassman made his living laying tiles in private homes and was very active in Hoboken in the 1960s. “I was Mayor Grogan’s confidential aide,” he says.

As soon as he returned from Korea, he joined the American Legion in Hoboken, where he served as commander and has been active for 65 years. “It gives me time to get acquainted with veterans who are still around and active,” he says. “We talk and reminisce. The Legion does a lot of nice things for America, and I’m for that.”

He’s got a lot of medals displayed in his home. “I just got a medal from the Korean government a month ago,” he says, “a beautiful one.”

Wassman, who will turn 92 in April, has 11 grandchildren. “It’s impossible to keep up with the younger generation,” he says. “Things move too fast. I wish they would slow down, so I could catch up.”

He marvels at the tiny phone he’s talking on. “It’s a little black phone, about an inch or an inch and a half.

“My memory’s not that good anymore,” he claims.

Judging from our conversation on his little black phone, his memory’s just fine.

Total Recall

Roy Huelbig sounds a lot younger than his 93 years. He’s got great hearing, a great memory, and a disarming (pun intended) self-effacement when he talks about the war and the old days. He signed on at 18, as soon as he was eligible, and served until 1946, when he was 22.

Embarking from Hoboken, his ship landed in Scotland. From there, he went on to Trowbridge, England, for basic training.

He was an Army Corporal. “Like Hitler,” he jokes.

“I was in the Calvary Group,” Huelbig says. “We went out on ships and armored cars to find the enemy and report back to the infantry. They came up and wiped them out.”

He says they went from the French city of Cherbourg to Brest in Brittany, where there was a big Nazi submarine base.

“We found the enemy,” he says, “and someone else had to shoot them. We did not have too much fighting.”

He was almost involved in one of the most famous battles of the war: the Battle of the Bulge.

“We were young guys, and we were scared, but we didn’t know any different,” he says. “As a matter of fact we were with Patton for one month in southern France.” That would be General George S., made even more famous by George C. Scott in the eponymous 1970 movie.

Patton “was a pain in the ass,” Huelbig says. “The first thing, he got up and said, ‘a lot of you guys are going to die.’ We were 18 years old. He scared the hell out of us.

“We rushed up to the Bulge,” he relates, “and when we got there, they didn’t need us.”

Instead, he was wounded in a town in Germany.

“I was hit in the leg twice,” he says. “Artillery shells split up and spin around the room.” They were sleeping in a building. “The shells came right through the building, split and spinning, shrapnel all around,” he recalls. “There were three of us, myself and another kid, 17 years old. The kid got hurt pretty bad, but he had no wounds on his body. He died from a concussion from the artillery.

“In March of 1945, I was shipped back to a hospital in England, when the war ended.”

Huelbig says he wasn’t too bothered by his wounds when he got back to Hoboken. “But I didn’t do much of anything,” he says. “I was like a bum.”

That is until 1948 when the Hoboken Fire Department took him on, where he stayed for 25 years. “It was a great job,” he says. “When we were growing up, the houses were wooden, shacks really. As time went by, groups would come and try to buy people out. If the people wouldn’t sell, the bastards burned them out.”

Huelbig says that in the early 1960s, hundreds of people died in arson fires.

“When we were kids in Hoboken,” he says, “we couldn’t afford rent and moved every couple of months.”

Times have changed. “It’s OK,” he says, “but it’s not Hoboken.”

It’s not just the big, expensive highrises on the waterfront that get his goat. “One of the biggest problems is women with baby carriages,” he says. “It’s a serious thing. They go right out in front of drivers and get mad when a driver doesn’t stop. The mother’s on the phone, afraid she’s going to miss something. Someone has to take responsibility.”

Taking responsibility was a hallmark of his generation, whether it was on the battlefield, in a burning building, or on a Hoboken street with a baby stroller.

“The world is crazy today,” Huelbig says. “It’s actually scary. I think we should take our allied troops and wipe out ISIS. It’s a whole different thing. They have no respect for anybody. They go into places and kill women and children and think nothing of it.”

Oh, and did I mention that Roy Huelbig was awarded the Purple Heart?

“It was about being stupid,” he says, “and getting wounded.”—Kate Rounds