In July of 2010, Natasha McNight-Henderson of Jersey City was 38 years old and finalizing her first adoption — a child whose mother had died and later ended up in a cousin’s custody, a frequent occurrence due to courts’ preference to place children with family members.

Two years later, at an adoption party for her second child, Jomaine, now 6, a friend and case worker asked McNight-Henderson if she’d be open to adopting two more children who’d just entered the system.

“I was like, no,” Natasha recalled. “I can’t now. But they said I would be good with them, so I said, OK, let me meet them.” When the worker told McNight-Henderson the girls’ names, Nyah and Desire, she said, “I just dropped and cried … those are my nieces, my sister’s kids, but I thought my aunt had them … but they went into the system.” Their names are now Ca-hya and Ya-nae. “It’s such a good thing,” McNight-Henderson said.

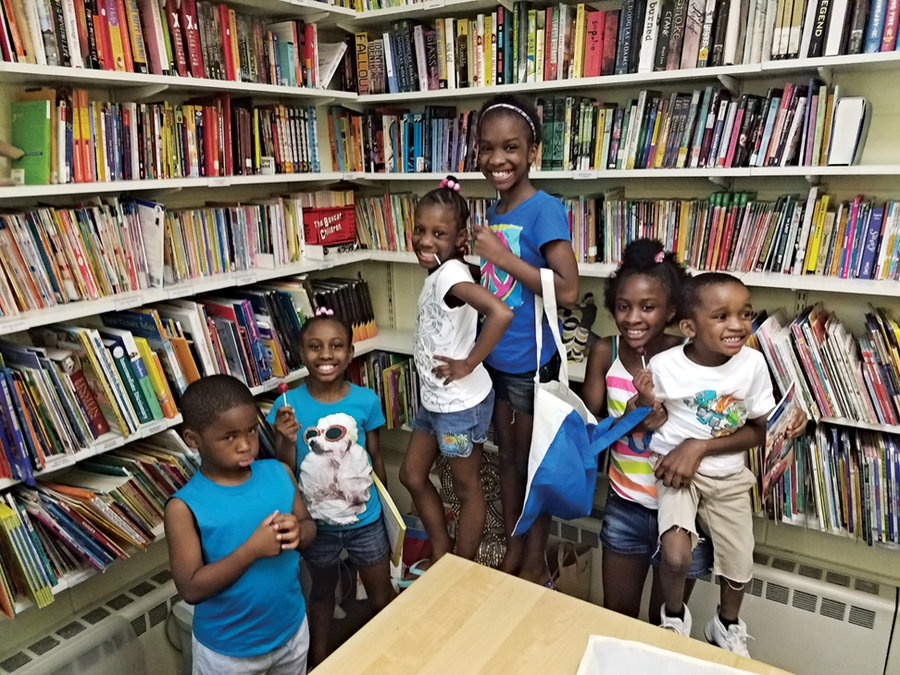

McNight-Henderson and her kids frequent the Hudson County CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocates) office in the Journal Square neighborhood of Jersey City, the non-profit organization that first trained her as a volunteer. The group recently added a library of donated books for children to take home.

“When I say CASA, they get excited,” she said. “Oh books, we got more books?” Jassmani, 11, picked out a mystery book, her favorite.

CASA of Hudson County attracts volunteers throughout the county, from Hoboken to Union City to Secaucus to Weehawken to Bayonne. With social workers spread thin these days, the volunteers – of all walks of life, ages, and marital status – have done an important job advocating for kids in the foster care system in Hudson County. Some work with the kids until they can return to family, and some end up adopting them.

From all over

John Sullivan, a retiree from Bayonne, has been a child advocate since 2007. What attracted him to CASA was not only the rewarding nature of helping children. “I have time on my hands and wanted to do something good,” he said. “The flexibility appealed to me, too.”

After he took a 30-hour course through CASA, he became a foster parent, dedicating his time to finding children permanency and/or reunification with family.

“I was somewhat of an abandoned child also from my mom, so I know how that feels, to have nobody there for you.”—Natasha McNight-Henderson

____________

“The father didn’t even know his child, but wanted custody. I had to talk to him,” Sullivan said. He added that it’s a great responsibility and anyone looking to become an advocate needs to be ready for anything. “You just don’t know what your role is going to be,” he said. “But CASA is always, always there.”

Natasha with the kids, or Auntie Tasha

McKnight-Henderson is a biological mother of three, a foster parent, an adoptive mother of six, and a certified “school mom,” according to an appreciation certificate awarded to her by the students at P.S. 14 in Jersey City, where she donates much of her time. Even before she took classes with Child Protection and Permanency (CPP), New Jersey’s child protection and welfare agency (formerly DYFS), she was a de-facto foster mother. “I always kept people’s kids,” she said. “It’s my role in the community.” She’s even known fondly as “Natasha with the kids.”

McNight-Henderson did not fall into foster care or child adoption by accident. “I honestly think that I’m good at it, and I always loved kids,” she said. “I was somewhat of an abandoned child also from my mom, so I know how that feels to have nobody there for you.”

The McKnight-Henderson family is happy, to a degree that can seem effortless to an outsider, but McNight-Henderson says it’s not easy, and connecting with a child who has a history of abuse is tough. Because Jassmani was not accustomed to moving around, McNight-Henderson said, “The one-on-ones were really important.” McNight-Henderson described her process getting through to Jassmani:

“I say, ‘Tell me why you feel this way. If you’re angry, want to punch something. Go ahead, hit me. Just let it out.’

She says, ‘I don’t want to hit you because you’re too nice to me.’

‘But don’t you want this?’ I ask.

‘Yeah, but I want my mommy,’ she says.

“I understand,’ I say, ‘but let me tell you what your mommy is going through.’

She says, “I know. I seen her at school. When they took us they told us. I know where she is. Mommy will always be mommy.’

They call me Auntie Tasha.”

The success of the McKnight-Henderson household is a testament to the efficacy of the CASA organization in navigating a system of cyclical poverty. Children in this system are victims of abuse or neglect, and CASA helps to find them permanent and stable homes.

McNight-Henderson calls CASA a “blessing.”

In Hudson County, 78 percent of the children that come through CASA have a parent or legal guardian in jail. Since African-Americans make up 1 million of the total 2.3 million incarcerated people in the country and outnumber their non-African-American counterparts in prison by a ratio of 12:1, it is not surprising that two/thirds of children who come through Hudson County CASA are African-American.

Drug addiction is most often at the root of the abuse or neglect that lands children in foster care, where the average child spends two years and changes homes three times. That is where organizations like CASA and its 75 volunteers in Hudson County come in. Its mission is to recruit and train children’s advocates, while being the eyes and ears for the court to ensure that children ages 0-21 are cared for. For each case, it has a court order to look at every facet of a child’s life. That information is used for court reports to inform judges’ decisions.

Patience, love, and affection

Currently, the program has 221 children, out of which 52 have permanent homes. Every home needs to be repeatedly vetted; every three months the child’s case goes back to court. Ninety-seven percent of CASA-recommended homes are converted to court-order, so CASA holds a lot of sway over where a child ends up. In order to make the arrangement financially feasible, the state gives a monthly stipend to foster parents. If they adopt they receive a continuing stipend. Natasha McKnight-Henderson says patience, love, and affection are necessary qualities in a successful child advocate. “Never think of yourself,” she said. “It’s all for the kids.”

CASA holds monthly information sessions the first Tuesday of the month at the Hudson County courthouse at 6:30 p.m. CASA can be reached at (201) 795-9855.