You would think that after all the times I had to go to the principal’s office as a kid, I would know how things are run. But my recent stint as principal for a day at Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Public School 11 taught me differently.

Being a principal is a little like riding a wave. You make plans, you have a routine, and you know where you need to get to by the end of a day. But ultimately, you’re reacting to continuing issues that arise from moment to moment. Somehow with routine, experience, and sheer fortitude, you get through the day.

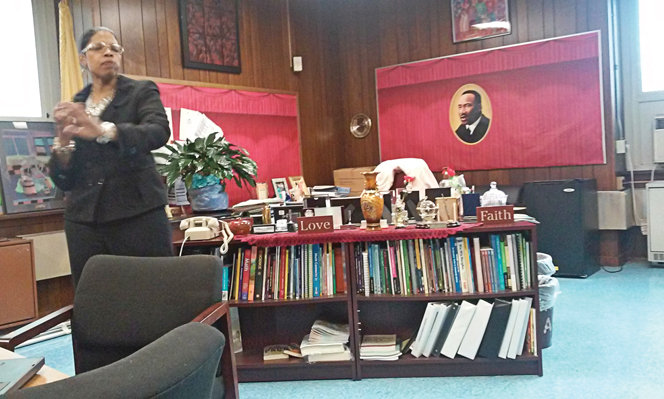

Shadowing Principal Cleopatra Wingard, I served as one of about 40 Jersey City residents who got a glimpse of the inner workings of the principal’s office that my previous experience had never allowed.

From morning announcements to finally sitting down to paperwork in the afternoon, Wingard has a hefty schedule.

The idea behind the Principal for a Day program sponsored by Silverman development is to allow the general public to view the school operations from the perspective of the principal.

“Most of our students come from working class families who are very interested in the progress of their children.” – Cleopatra Wingard

____________

A historic school with a historic name

P.S. 11, located on historic Bergen Avenue just south of Journal Square, is one of the oldest schools in Jersey City, rebuilt after a fire in the 1960s, and named after one of the great civil rights leaders, The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King appeared at St. Peter’s University in 1968 and was assassinated that same year, the year the corner stone of the new building was laid.

Ironically, Principal Wingard, who took the post three years ago, is the school’s first African-American principal.

Also ironic is her first name.

“My parents were into history,” she said.

The school she oversees has a significant population of immigrants from Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries. Many of the students speak Arabic as their primary language.

“Most of our students come from working class families who are very interested in the progress of their children,” she said.

Indeed, this is reflected in the turnout on report card nights, when parents come to talk with teachers about the progress their children are making.

Even though the school has a student population just shy of 900, more than 1,000 people showed up for first report card night in the fall.

“This is because whole families came to that one,” Wingard said.

It was the first report card night of the school year, so many family members wanted to meet the teachers. But even subsequent report card nights drew 800 visitors.

Parents are very involved. This is also evident on school day mornings when often parents come before the start of the school day to meet with teachers.

“We start at 8:30 a.m. and I encourage parents to meet with the teachers during the half hour before school starts,” Wingard said.

An early start each day

For Wingard, however, the school day often begins before she leaves home. She often texts directives to school personnel who actually start working as early as 7 a.m.

While her contract stipulates her work day as 8 to about 4 p.m., she is at the school until five or even later. Some nights she’s there until after 7 p.m.

“There are things I need to do,” she said.

Sometimes people need answers and would call her at home anyway. So she stays at school to answer the questions.

Since the school is host to the once-a-month meetings of the Jersey City Board of Education, she stays for part of the meeting.

“I look around the audience to see if there are any parents of our students,” she said.

Although she tries to resolve all issues that might come up, she said she doesn’t want to hear second-hand a complaint raised at a Board of Education meeting.

A chain of command

While she owes a debt of gratitude to Superintendent Dr. Marcia Lyles for her position as principal, Wingard is overseen by Dr. Michael A. Winds, director of Division A schools.

Jersey City has four divisions, each with a director. Principals report to these directors and these directors report to the superintendent.

But for some matters, Wingard said she will copy her communications to Lyles, especially if it is an issue that may affect the whole district.

Principals also interact with the directors of various departments, such as Early Childhood, Curriculum and Instruction, Special Education, and others, since these offices are usually consulted by the division directors.

In Jersey City, principals have a lot of latitude, as long as they follow guidelines of CORE curriculum and other regulations.

In P.S. 11, teachers likewise have a lot of discretion when designing programs for their children.

Creativity is encouraged as long as it enhances a student’s ability to meet state and federal standards.

In one class, the Harry Potter novels were being used, not just to learn reading, but to engage student’s ability to reason. In another class, H.G. Wells’s “Time Machine” was being used to help students learn how to read and speak English.

Many of the students speak, read, and write Arabic. These students often excel in mathematics, but struggle with overcoming the language barriers. Multi-lingual teachers help bridge the gap. But these students are often very motivated, and learn quickly, often leaping ahead once they overcome the language issues.

But sometimes language is an issue when reaching out to their parents. In many cases, important notes sent home to parents are translated into Arabic.

Good morning, students

A principal in P.S. 11 begins the official day by greeting the younger children in front of school.

Parents are discouraged from simply dropping off students at the curb. But when they do, a security guard helps the kids onto school grounds. Students line up according to class. The teacher comes out, and then escorts them into the school.

Wingard often waits for stragglers to make sure all get into the school safely.

Once students are in school, Wingard makes a general announcement. On this day, she announced that I was principal for the day, and that she and I would be touring classrooms.

This tour of the school is something Wingard does every day, walking more than two miles each morning.

While every principal has a different approach, Wingard likes the students to see her around the school. If she can’t make it for some reason, she has other administrators do it.

This allows students to see them and sometimes interact. These interactions positively affect student attitudes during the day.

“I don’t know all of the names of all of the students, but I know their faces,” she said.

More importantly, the students know her. Many of the younger students hug her when they see her in the hall or cafeteria.

Normally during morning announcements, a younger student gets to lead the school in the Pledge of Allegiance over the public address system. Usually it is a different student each time, and for that day that student becomes something of a celebrity.

While Wingard has a routine she follows daily, she is constantly interrupted. Parents show up at the counter. Teachers stop her in the hall. Administrators have issues that need to be resolved.

On this drizzly Thursday, Wingard is concerned with two field trips that scheduled for the next day. With the forecast of steady rain, she has to determine if the event has to be rescheduled. This involves not only the location to which the students are going, but the bus transportation to get them there.

But there are many other issues that come up during the day that often require her attention, some more serious than others.

Some involve mischievous students, five or six very bright overachievers, who usually create a bit of controversy every day.

“We always hear about them,” Wingard said. “If we get through a day without hearing about them, we later find out they were not in school that day.”

These are usually relatively innocent infractions of rules or social order that teachers and administrators have to deal with.

“I don’t like issuing suspensions,” Wingard said. “These usually affect school work.”

She, a teacher, or a member of the guidance department talks to the student.

One small incident occurred in the cafeteria on my tenure as principal for a day, recalling some of my own antics at that age.

“He’s just discovering girls, so he’s showing off,” Wingard said.

Getting a taste for education

Wingard grew up in Newark, where she attended Kean University, and eventually went on to get her masters degree. She is currently working on her Ph.D. at St. Peter’s University.

Her mother is a teacher in the Jersey City school district. Watching her mother work at home grading inspired Wingard to seek a career in education. She started out as a teacher, but eventually got a taste for administration.

“I ran a summer program one year,” she said.

She realized that she could better shape the direction of education as an administrator. She eventually became an assistant principal at another school in Jersey City, and finally was named principal at P.S. 11.

“When I got the position I came to the school before I actually started,” she said.

She saw the name “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.” and then the corner stone with the year “1968.”

“It chilled me to see that,” she said.

Part of that was history, and the role she was to play as the school’s first African American principal.

But she soon discovered other bits of history hidden behind boxes in what serves as the principal’s office. This included a diploma issued in 1917.

“Apparently the student wasn’t here for graduation and never picked it up,” she said.

On the tour of the school, students greeted me as if I really was a principal, rather than the self-taught high school dropout whose previous visits to the principal’s office came as a result of some prank.

From youngest to oldest, the students seemed incredibly focused.

“The younger kids are the ones that act out most,” Wingard said. “But their parents deal with them. The parents want their children to show respect. If there is a disagreement with us, they parents will deal with it. They don’t want their children showing disrespect.”

Many of the key teachers in the school have been there for decades, and Wingard said she relies on them because they have experience and knowledge that administrators lack.

“These teachers were here before we came and they will be here after we are gone,” Wingard said. “They are what make this school what it is.”

But this is also true for many of the other employees such as those involved in maintenance and security.

“What makes this school special is that we are like a family,” Wingard said. “We have parents who really care about their children’s education.”

Al Sullivan may be reached at asullivan@hudsonreporter.com.