These days, Hudson Lanes, which straddles the border between Bayonne and Jersey City, is about the only game in town. But back in the day, bowling lanes were like corner bars; they were everywhere. Well, not quite. Donna Massa, secretary/treasurer of the Strikes R Us women’s bowling league, recalls 40 years of bowling.

“When I was a kid, I started bowling at Assumption Lanes on 23rd Street between Kennedy Boulevard and Avenue C,” she says. “Where McDonald’s is now on 25th and Broadway was a Dewitt theater, and it also had bowling lanes. The Moose Lodge between Broadway and Avenue C had lanes. On 53rd Street where Value City Furniture is now was a bowling center. Knights of Columbus on 30th Street had six lanes, and Roosevelt Lanes was in Jersey City on Route 440.”

She also recalls Bayonne bowling being mentioned in an episode of “The honeymooners.”

That may or may not be true, but Ralph and Ed were members of the Order of Loyal Raccoons and did invoke a “Raccoon from Bayonne.”

Massa’s father used to fix the machines at the Assumption Lanes. “I would go with him sometimes and bowl,” she says. In fact, for the Massas, bowling is a family affair. Both daughters bowl, and Massa’s husband bowls with the Mt. Carmel men’s league. Hey, she explains, “there’s not much to do in Bayonne.”

The Strikes R Us women bowl every Monday night, September through May, from 6:45 to 8:30. After bowling, it’s off to the Starting Point for pizza. “We go from one end of Bayonne to the other,” Massa jokes.

At the end of the season, they have an awards brunch at Winners.

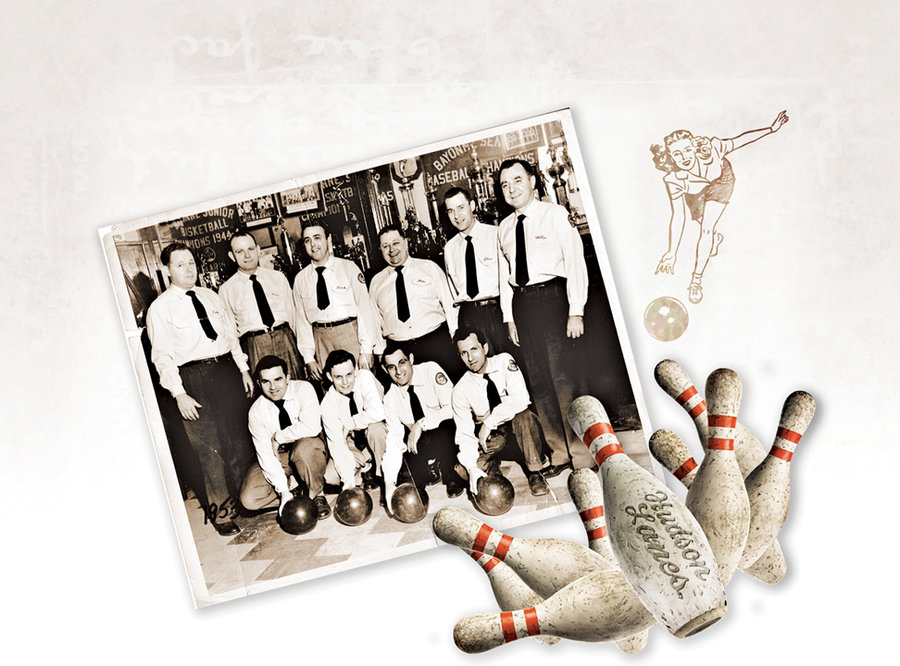

Bowlers and Bus Drivers

Mike Peregrin is an officer with the Lyceum Bowling League. He also remembers the Knights of Columbus and Moose Lodge lanes. He pegs bowling’s popularity to its “blue collar” cred. He, too, invokes Ralph and Ed. “They were bowlers—a bus driver and a sewer worker—you can’t come up with a better example of the relationship between bowling and the blue-collar life,” Peregrin says. In fact, Massa’s husband, Emil, also has a connection to the bus industry. He manages the Broadway Bus company.

“It’s a fairly cheap sport,” Peregrin says, “which also plays into the blue-collar side of it.”

Peregrin emphasizes the fellowship of bowling. Lyceum bowlers are part of the Mt. Carmel Lyceum Catholic men’s organization, which is connected to the church. The bowlers are “practicing Catholics,” he says.

Bowling is also popular, he posits, because it doesn’t matter how old or how good you are; as in golf, it uses a handicap system. It’s a social sport, too, with snack bars and booze. “Beverages help to encourage the social side,” Peregrin says delicately.

“For the most part,” Peregrin says, bowling is “fun-natured and not a cutthroat situation, where you are getting upset with other people. We stress brotherhood. We’re there to have a good time and not forget the true meaning.”

The Lyceum bowlers raise money for charitable events, scholarships, and contributions to the church. For years, it ran an instructional league for kids on weekend mornings.

Bowling for Dollars

Retired from the board of the U.S. Bowling Congress, Clare Schroder bowled at Snyder High School in Jersey City and now runs bowling leagues for kids.

“I can’t remember a year when I did not have a disabled youth of some sort in the league,” she says, mentioning kids on the autism spectrum and a boy with brain damage. An adult in the Family Fun Youth Adult League is an excellent bowler, even though he’s blind.

Kids as young as 2 can bowl with the help of a “dinosaur ramp” that allows them to push the ball, and bumpers that keep the ball out of the gutter.

“Some kids are bullied because bowling is considered a sissy sport,” she says, “but it’s the only sport where kids can earn scholarships.”

Out of the Gutter

John Rokicki, who was a past president of the Knights of Columbus league, laments what he says is “lost participation.”

He blames—you guessed it—the digital age. “A lot of people in the computer era stay home instead of bowl,” he says. “It’s dying a little bit because of the internet and video games.”

But there’s no death in his family. “Three generations in my family bowl together,” he says.

Peregin agrees. “Recently I was bowling with my 11-year-old son,” he relates, “and an older guy pulled me aside and said that I was doing the right thing by spending time with my son and keeping him away from trouble on the streets.

“It made me feel good because he was right.”—BLP