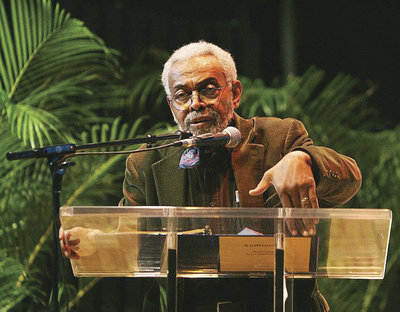

A decade after he forced poet Amiri Baraka out as poet laureate of New Jersey, former Gov. Jim McGreevey mourned the poet’s passing.

Baraka, who died on Jan. 9 at age 79, was seen as one of the last voices of the radical Black Power movement of the 1960s, and a man who retained his radical roots in his home town of Newark.

Baraka had warned McGreevey that naming him to the post of poet laureate in 2001 might bring controversy. A year later, circumstance and protests from the arts community forced McGreevey to ask for Baraka’s resignation after the poet published a controversial poem about 9/11, a poem Baraka continued to read even though some of the information contained in it was proven to be inaccurate.

The confrontation in 2002 was not personal, McGreevey said.

McGreevey, along with many of the state’s art elite, were outraged by a 9/11 poem Baraka read at the 2002 Dodge Poetry Festival slightly more than a year after the terrorist attack brought down the Twin Towers and destroyed a portion of the Pentagon, resulting in deaths of thousands of innocent people.

Baraka questioned whether Israel knew in advance of the attack on the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001 and whether the nation deliberately ordered its citizens to stay away from the buildings.

Baraka’s remarks came in the middle of a poem several hundred lines long, part of a questioning process as to who knew what about the attack.

“There is a difficult tension in people who are creative and those who make public policy. Amiri was in a different place.” – Jim McGreevey

____________

Baraka offered no apology, claiming that the U.S. government was well aware of the attack before it happened. Baraka believed the United States and others were seeking to use the attack as an excuse to crack down on unfriendly governments in the Middle East.

The line was based on a website claim that was later proven to be inaccurate.

At the time, McGreevey was besieged by complaints, but a decade later, he said he understood the conflict between art and government.

“There is a difficult tension in people who are creative and those who make public policy,” said the former governor, who now heads Jersey City’s jobs commission. “Amiri was in a different place. It was my mistake to ever think that he would feel compromised by the state designation. He did not want to compromise his art.”

Amiri was a radical in the truest sense of the word, defying convention when he found convention generated inequality, especially when it came to race.

Over the years, Baraka continued to read the poem as a kind of personal protest, something he commented on during an appearance at Jersey City Library in the Greenville section a few years later. Baraka’s firing became a symbol of the limits of free speech for many.

The benefit of hindsight and time’s passage

But in marking Baraka’s passing earlier this month McGreevey called the poet “a great artist.”

“He was exceptionally gifted,” McGreevey said. “I named him poet laureate because I appreciated his art, his intelligence and his creative energy. I’ve always had great personal affection for him and recognized him as a gifted creative force.”

While McGreevey and Baraka did not make public peace, they shared mutual friends, and McGreevey understood Baraka’s position.

“As governor, I had to deal with the responsibility of my office,” McGreevey said. “People who cherish his work also admire his artistic freedom. The position of poet laureate created a conflict in his creative license. He saw that as something sacred. He understood things from a different perspective. It wasn’t in him to compromise. But his loss is the loss of a great artist.”

McGreevey said he understands the radical side of Baraka. And remarkably, over the last decade, McGreevey has moved closer to the place Baraka occupied, working with many of the same people.

In Newark, even hardened street gang members would step aside on the street out of respect for Baraka, knowing that his voice represented many of those who had no voice of their own in an unfair community.

“I consider myself radical,” McGreevey said, citing his work with many of the same prison population Baraka represented in his work.

“When one out of every 100 people is in prison then there is something radically wrong with the system,” McGreevey said. “This should put us on notice that we are failing.”

McGreevey laughed during a telephone interview at the irony of his winding up in the same sphere as Baraka.

“Maybe this is his best revenge,” McGreevey said. “He’s bringing me over to that place.”

Payne pays tribute to Baraka as well

Rep. Donald M. Payne, Jr. who represents Newark as well as parts of Bayonne and Jersey City, paid tribute to Baraka as well, calling him “an icon”

“Born during the Depression, at a time when racial tensions were at their peak, Amiri Baraka used poetry to empower and enlighten,” Payne said. “He eventually founded the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, and received countless awards for his contributions to the arts. My father and he attended school together, and I’ll never forget as a youngster, hearing Amiri Baraka’s poetry, and recognizing the power his written words had over a person – regardless of age, gender, or race.”

Baraka, as McGreevey also noted, was not only a poet, he was an activist. In 1969, he organized the Black Puerto Rican Convention which brought those communities together at a bleak time. He was also one of the main organizers and the keynote speaker at the 1972 Black Political Convention in Gary, Ind.

“His profound words were influential as many searched for meaning in some of the most troubling struggles of our time – like civil rights, war, oppression, and poverty,” Payne said. Later, he taught at SUNY Buffalo and SUNY Stony Brook, giving his talents to a new generation of poets, artists, and activists.”

Al Sullivan may be reached at asullivan@hudsonreporter.com.