When Hoboken High School’s Emergency Response Team course was disbanded at the beginning of the school year, it shed light on the work of one of Hoboken’s most important institutions: the Hoboken Volunteer Ambulance Corps. These students were certified as first responders and emergency medical technicians (EMTs), who assisted the corps in answering 911 calls around the city.

The loss of the program was heartbreaking for the students involved, but nothing can dim the brilliant work of our ambulance corps.

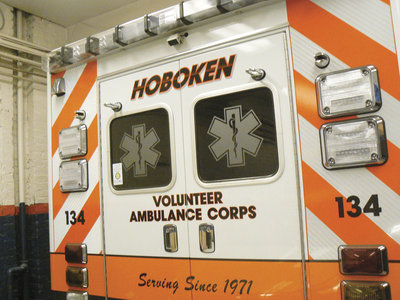

Ambulances—like fire trucks—are probably the most valued vehicles in town, but a lot of folks may not know that that ambulance speeding through the Hoboken streets to save a cardiac-arrest victim is staffed entirely by volunteers.

The Hoboken Volunteer Ambulance Corps, which was established in February of 1971, provides the emergency medical services for the city of Hoboken. “We don’t get paid, and we don’t bill,” says Thomas Molta, president of the corps. “We are a volunteer organization that provides to the city for free.” Molta, who has been president for 21 years, joined the corps when he was only 16.

The corps has 188 members and three life-support ambulances.

Becoming an EMT who rides in the ambulance is a rigorous process. Applicants take a 220-hour course to be certified for hands-on patient care. A minimum of two and a maximum of four ride in the ambulance. The driver needs specialized defensive-driving instruction to become a Certified Emergency Vehicle Operator.

Molta has spent his working life in the business of helping people. He retired from the Hoboken Fire Department as a captain.

Ambulance corps volunteers are a diverse group. “They come from all different walks of life,” Molta says. “Doctors, nurses, electricians, Wall Street lawyers…”

The age range is 16 to the early 70s; they are required to work four shifts per month. The ratio of male to female it two to one male, and you have to be able to lift a 165-pound person onto a stretcher.

Molta has an encyclopedic memory for fires—even those that occurred before his tenure at the corps. “The Pinta Hotel fire on April 30, 1982; we lost 14 people in one building,” he recalls. “In January 1979 at 131 Clinton St., 21 kids were killed in a fire. It was a huge loss of life in a five-story tenement building.”

Since he joined the corps in 1980 he’s seen his share of disasters. “All the fatal fires in Hoboken—multiple-fatality fires,” he says. “There was a major one at 1200 Washington St. in 1981 where 12 people died. There were multiple injuries and fatalities. These people were on fire and jumping out windows.”

He said the corps was on hand for the first World Trade Center bombing in February of 1993. “We treated 165 people in Hoboken who came over on the ferries and PATH train or on buses,” he says.

Eight years later, on Sept. 11, 2001, the corps treated more than 2,000 people.

The less spectacular events are no less important to the volunteers in the ambulance corps. Molta says, “We have had multiple storms, blizzards, nor’easters, and train derailments.”

The ambulance has been on the scene during hazmat incidents. On Oct. 4, 2002, there was a chemical leak at the Cognis Corporation at 1301 Jefferson. “Chemicals were releasing acid, and we stood by on that one,” Molta says.

“For any emergency that occurs in the city, we are the service provider,” Molta says. “A few years ago a helicopter and a plane collided over the Hudson, and we were there during the post- 9-11 blackout in the northeast corridor.”

Various injuries and disasters affect EMTs in different ways. “For me it’s kids,” Molta says. “Personally I hate hearing when it’s kids who get injured or sick. They have a special place in my heart. For some, it’s the elderly—when my mom passed away from Alzheimer’s, it touched me. Everybody’s different.”

But not everybody is cut out to be an EMT—that man or woman who courageously answers the call, not knowing what injury, illness, or accident he or she might have to face.

A person can meet all the qualifications for being an EMT but still not be right for the job. “They might see someone really banged up or bleeding and freak out, and say, ‘This isn’t for me,’” Molta says.

There is no dishonor in knowing that you can’t hack the work. The important thing, Molta says, is to acknowledge it and not jeopardize the lives of the crew or the victims.

Molta says that good-hearted people are drawn to the work because it is unpaid, and they can give back to the community. “They have to be compassionate and willing to learn and adapt,” he says. “A situation can change from normal to really bad in a split second. They have to think fast and be quick on their feet.”—07030

Photos by Kate Rounds