If Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop is padding his resumé to run for higher office, perhaps governor, in a few years – as has been widely speculated – he will likely want the endorsement of a few labor groups. Thus, it is not surprising that Fulop, both as Ward E city councilman and as mayor, has advanced a number of proposals to protect the rights of workers.

Last year he introduced a “living wage” ordinance that was adopted and increased wages for security guards, janitors, food service, and clerical workers at city-owned and city-leased offices. Earlier this month he endorsed a ballot initiative that would boost the state minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $8.25 an hour.

Last week, Mayor Fulop scored his biggest labor victory to date when Jersey City became the first municipality in New Jersey to adopt an earned paid sick leave law.

Under the law, private businesses in Jersey City with 10 employees or more must begin to offer one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked (those are hours worked overall, not per week). Workers begin earning sick time from the day they were hired, but cannot begin to use their sick time until they have worked the equivalent of 90 eight-hour days, which is the standard probationary period at most companies.

While the law technically applies to part-time and full-time workers alike, it will take part-timers longer than full-time employees to meet the required threshold to begin earning days.

Supporters of the law say that it will stop workers from forcing themselves to work when they are sick, and will benefit companies and customers as a whole. For instance, earlier this month, at least 27 people came down with mumps in Belmar, and officials speculated that the source of the outbreak was a bar and grill there. It has been suggested that the outbreak may have been spread by workers who continued to show up and handle food and dishes while sick.

The bar was shut for several days to prevent further infections.

Critics of the law, however, say that it will hurt small business in the city.

Details of the law

Workers can earn up to five days per year, and the law, which takes effect in 120 days from when it was passed, does not allow employees to cash out any unused sick days when they leave their jobs.

Companies with fewer than 10 workers must offer job-protected unpaid sick leave to their employees.

The law received broad support from workers’ rights and labor groups, but divided the business community. Some small business owners said last week that a paid sick leave law “makes good business sense,” while the manager of the Central Avenue Special Improvement District said the law will hurt small businesses and start-up companies.

In the end, the Jersey City Council adopted the controversial measure by a vote of 7-1-1. The measure gained the support of council members Frank Gajewski (Ward A), Khemraj “Chico” Ramchal (Ward B), Candice Osborne (Ward E), Diane Coleman (Ward F), Daniel Rivera, Joyce Watterman, and Council President Rolando Lavarro Jr.

Ward C City Councilman Richard Boggiano abstained. Ward D City Councilman Michael Yun voted against the ordinance.

“Paid sick leave will help working families in Jersey City so they won’t have to choose between missing a day of work and caring for their own health or that of a family member,” Fulop said in a statement issued after the measure passed. “Not only is this a matter of basic human dignity, it is also a public health initiative that will benefit all Jersey City residents as well as those who work here. We commend the City Council for voting in support. We know that we will be sued over this legislation, which is disappointing and harmful to Jersey City. It means delaying these important benefits to those most in need while at the same time not enhancing public health in the city.”

A first in the state

Although similar laws have been passed in other states, Fulop’s sick leave measure is a first for New Jersey. According to New Jersey Citizen Action, more than 30,000 Jersey City workers do not have access to paid sick leave.

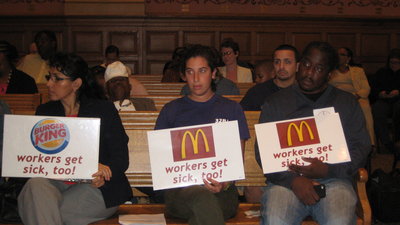

Dozens of residents and advocates told the council grim stories of what can happen when sick employees show up for work because they can’t afford to lose a day of pay or can’t afford to lose their job.

Jersey City resident Paulette Eberle told the council that her elderly and frail father was recently admitted to Christ Hospital because one of his home health care aides attended to him while she was infected with the rhinovirus.

“I would like to be angry at this aide and I cannot because the reason she came to my father in that condition is because she has a choice to make: feed her children or stay home,” Eberle said. “In this millennium, that is not a decision that any of our citizens here in Jersey City should have to make.”

Such decisions are common, said Ady Barkan, a staff attorney with the Center for Popular Democracy. Barkan told the council that, “People without paid sick days are 1.5 times more likely than people with paid sick days to report going to work with a contagious illness like the flu or a viral infection.”

Several speakers pointed to the recent mumps outbreak in Belmar as an example of what can possibly happen when people show up at work sick.

‘Common sense’ or ‘extremely flawed’?

Jersey City’s small business community appears divided on the law and its likely impact on the local economy.

Phillip Stamborski, owner of Gallerie Hudson at 197 Newark Ave., was among the small business owners who spoke in support of the measure.

“I only have two part-time employees. If one of them gets sick, I’d want them to stay home and get healthy. I can’t afford to have them come to work and get me sick, or get my other employee sick. If I get sick, and have to stay home, I have to close the store and I lose revenue.”

Stamborski said he is unable to offer paid sick leave at this time, but when employees miss work hours one week due to illness he tries to give them additional hours the following week to make up for the lost pay.

Under the measure adopted last week Stamborski would not be required to offer paid sick days, only job-protected unpaid leave. As his business grows he said he plans to give his workers paid sick leave because, he said, “it makes sense to give people paid time off. It makes sense to keep loyal employees.”

Steve Kalcanides, the owner of Helen’s Pizza at 183 Newark Ave., also supported the measure, saying, “There is no way the ordinance should not be passed,” he said. “These are common sense guidelines that every business should have for their employees. If you keep your employees happy, your business prospers. We’ve been in business for 45 years and we’ve always paid for time off, for sick days. What this ordinance is going to do is level the playing field for all the businesses.”

With an estimated 10 to 12 employees, by Kalcanides’ count, Helen’s Pizza would be required to offer paid leave to its workers.

The only person who spoke in opposition to the ordinance at the Sept. 25 City Council meeting was David Diaz, manager of the Central Avenue Special Improvement District in the Jersey City Heights.

“This ordinance will affect every single Jersey City business and is extremely flawed,” Diaz told the council Wednesday. “Jersey City’s business community does want the opportunity to contribute positively towards a better sick leave policy. Let me be clear: Businesses should offer sick time because of the reasons stated here tonight. Generally, speaking, no business owner who has come forward to our SID program is against employee earned sick time, paid or unpaid. However, a business owner’s desire to provide sick days and the ability to pay for sick days are two separate matters.”

Noting that there are currently 18 empty storefronts in the Heights, Diaz said small businesses continue to struggle in the post-recession economy. He asked that the ordinance be tabled so its affects on the business community can be studied further.

A motion to table the ordinance by Yun, a small business owner himself, was defeated.

Diaz predicted that the law, if passed, would put Jersey City at a competitive disadvantage in attracting new businesses.

But Tony Sandkamp, who moved his business from New York to Jersey City 15 years ago, said, “Looking back on my decision to move here, and looking at the ordinance, it would not have changed my decision to move here.”

Sandkamp has offered job-protected unpaid sick leave in the past but said, “I welcome the change.”

Can Jersey City lead the way?

Business groups in Jersey City and Hudson County have questioned whether a municipality has the authority to pass earned sick leave legislation. They have argued that such laws can only be adopted by the state legislature or the federal government.

It is possible that the business community will go to court to challenge the law that was passed in Jersey City last week.

Corporation Counsel Jeremy Farrell said that the city does expect a legal challenge to be filed, but Farrell said he believes passage of such a law is within the scope of the city’s rights as a municipality.

In the meantime, in May, New Jersey Assemblywoman Pamela Lampitt, who chairs the Women and Children Committee, introduced sick leave legislation in Trenton. State Sen. Loretta Weinberg introduced companion legislation in the New Jersey Senate. The legislators say the law would protect more than 1.2 million New Jersey workers who do not currently earn sick leave at their jobs. This number represents about 37 percent of the state workforce.

Labor groups and such organizations as the AARP have applauded Fulop for taking the lead on this issue.

“Mayor Fulop and members of the Jersey City Council deserve credit for taking the lead on one of the major workers’ rights and public health issues of the day,” said Kevin Brown, state director of the Service Employees International Union 32BJ.

The mayor’s stance on such issues now will likely garner strong labor support in the coming years.

City spokeswoman Jennifer Morrill said the city will notify businesses of the new law and its requirements.

E-mail E. Assata Wright at awright@hudsonreporter.com.