It has been 20 years since the discovery of environmental contamination at the Keystone Metal Finishing plant property on Raydol Avenue and Humboldt Place – yet officials say that further testing and remediation is still required to fully clean up the area.

During the Nov. 22 council meeting, the mayor and Town Council passed a resolution to apply for federal funding to conduct further testing of residential homes located within 100 feet of the plume of contamination and to perform further remediation.

The total cost of this new aspect of the project is $220,000. A federal Brownfields Assessment Grant would cover $200,000 of that total while the town would cover the balance.

“We are going to do everything we can do to be safe,” said Mayor Michael Gonnelli. “We want to make sure everything is clean and we want to fully remediate the site.”

“The assessment activities include a vapor intrusion investigation.”

____________

“Our goal is to get them all down to acceptable levels,” said Town Administrator David Drumeler. “From what everyone tells us…it doesn’t pose a hazard to the residents. Most of this is groundwater contamination. If we had wells it may be different. But it is much less of a concern because we don’t get our drinking water from wells in the ground.”

Town officials said in 2008 that the area posed no health threat to residents, and was within acceptable federal contamination standards. But residents fear that there is still a threat, and the stigma of contamination has potentially affected the ability to sell homes near the site.

According to Lawrence Hajna at the DEP, the main contaminant at the Keystone site is Tetrachloroethylene, or PERC. The chemical is widely used for dry-cleaning fabrics and metal degreasing operations. According to the EPA, the main effects of tetrachloroethylene in humans are neurological, liver, and kidney effects following acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) inhalation exposure. Results from epidemiological studies of dry-cleaners occupationally exposed to tetrachloroethylene suggest increased risks for several types of cancer.

Testing 60 homes

The municipality seeks funding to test 60 residential homes within 100 feet of the plume, which would cost $60,000. The remaining $160,000 would be applied to continued remediation that includes injections to help mitigate the contaminants, according to Drumeler.

The assessment and investigation would be conducted by BMG. The town has also applied to be a part of a pilot-study led by the University of Tulsa to test the usage and effectiveness of the chemical injections used to reduce the plume, a new method first used at the site in 2000.

According to the resolution, the assessment activities include a vapor intrusion investigation of the residences surrounding the site, and additional groundwater investigation to determine potential utility pathways for the migration of the contaminants of concern.

According to the NJ DEP, the presence of volatile chemicals in contaminated soil or groundwater offers the potential for chemical vapors to migrate through subsurface soils and/or preferential pathways (such as underground utilities), thereby impacting the indoor air quality of area buildings. Vapor intrusion refers to this migration of volatile chemicals from the subsurface into overlying buildings.

History

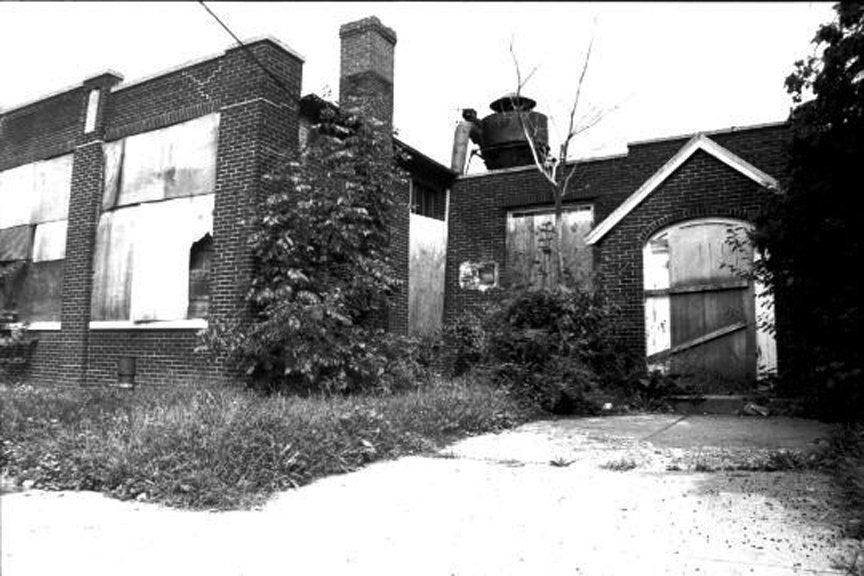

From 1947 to 1991, the Keystone Metal Finishing plant ran operations on their 1.37-acre property in a mostly residential area. In 1991, the town discovered multiple contaminants on the Keystone property such as cyanide, alcohol, hydrochloric acid, and other hazardous materials within 45 unsealed drums after metal finishing plant owner Joseph Karet died.

According to Lawrence Hajna at the DEP, the state requested the removal action of the contaminants and the EPA removed the drums of hazardous materials at that time. In 1992 the town of Secaucus took over property ownership. The town entered into a voluntary clean-up agreement with the DEP. The agreement was adjusted to include remedial investigations and actions in 1995.

During the demolition of buildings in 1996 a dry well was discovered that apparently had been used by Karet for the disposal of contaminants. A groundwater investigation was conducted at that time. Town officials learned in 1997 that contamination from the Keystone site had spread to several nearby homes and was present in deep level groundwater. Despite having this information, town officials, under the administration of former Mayor Anthony Just, didn’t inform the public or affected property owners. The information was not publically released until 1999, and mayoral candidate Dennis Elwell used it in his election to oust Just.

In 1999, the town conducted a pilot project followed by full injection and treatment of the contaminants in 2000 with a hydrogen releasing compound, a process which is known as bio-remediation.

After Elwell took office, the town spent $750,000 to remediate the land. In addition, a number of monitoring wells were installed to allow engineers to conduct ongoing tests of groundwater, both at the Keystone site specifically, and at off-site locations near some of the affected homes.

The town has continued to monitor the success of the remediation and any environmental impact of the contamination.

“The DEP has sent Secaucus a letter asking for an update on the status of how things stand,” said Hajna. “It does not appear that we have gotten any recent updates.”

According to Gonnelli the town plans to include the community in this next phase of remediation and testing.

“We would definitely have public meetings like we did last time just to tell them where we are [in the process],” said Gonnelli.

Drumeler said the town was committed to cleaning up the old Keystone site even if the funding from the EPA does not come through.

“We’ll continue to look for funding sources to help us clean it up,” said Drumeler. “It was an orphan site that we inherited. We didn’t get this property by any other method. We aren’t an owner in the chain. Obviously we’d like to clean it up as best we can.”

Adriana Rambay Fernández may be reached at afernandez@hudsonreporter.com.