It’s hard to believe that 19th century North Bergen could be such a different place.

Many residents who travel along Bergenline Avenue each day don’t realize that more than 100 years ago, the road was home to one of the most controversial race tracks in history.

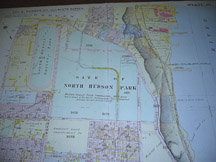

The Guttenberg Race Track, which was actually located in North Bergen, was a gambling haven back then. Located near the old Nungesser’s Hotel, the massive 71-acre lot ran between Bergenline Avenue and Third Avenue, which is now approximately 82nd Street to 92nd Street. The track hosted an average of six horse races per day.

Doors open

The North Hudson Driving Park Association originally established the lot as a trotting course, a half-mile track in which casual competition could take place.

When the state of New York outlawed racing in 1885, New Yorkers were forced to find a new place to pursue their gambling needs. They soon found a place at the Guttenberg Race Track, which was purchased by the Hudson County Jockey Club, a group comprised of both Hudson County and New York horse racing enthusiasts.

The Jockey Club renovated the facility and expanded the track to a mile. Its doors were open to the public in 1889.

Upon opening, “The Gut” quickly became a phenomenon known mostly for its continuous operation during the depths of winter.

Willing to brave any weather

Indeed, the track will perhaps go down in history for its perseverance through extremely adverse weather.

Heavy fog, rain, and snow were common during races. No matter the condition, the track would continue to hold six races every day.

The track gained a particular notoriety for its winter racing. An 1892 article in the Lewiston Evening Journal, which was based in Lewiston, Me., stated that the track would operate in three feet of snow, with temperatures registering below zero. Races would be held through torrential downpours and fogs thick enough to completely obstruct the horses and jockeys from judges and spectators. The track boasted the largest stable in the United States, which undoubtedly contributed to its ability to thrive outside whatever perils Mother Nature threw its way.

“The Gut,” a winter home to roughly 1,000 jockeys, stable boys, and trainers, would attract crowds of around 8,000 people per day, with the price of admission at one dollar. Purses of roughly $2,800-$3,000 were paid out each day. This purse would equate to approximately $70,000 today.

A rather rowdy reputation

Upon its inception, the Guttenberg track became known for attracting a certain type of crowd.

“There was a lot of controversy surrounding it [the track] in terms of the characters that were there,” said Damian De Virgilio, a member of the Hudson County Genealogical and Historical Society, last week. He added, “even also the kinds of businesses that may have sprung up around it.”

The 1892 LEJ article – which was published while the track was in operation – sheds light on the typical “Gut” crowd.

“The Guttenberg people, apparently calm in the assurance that they will not be seriously interfered with by the authorities of Hudson County, N.J., claim to be entirely indifferent as to whether the legislature does or does not legalize their money making business,” noted the story.

Indeed, the track had earned a reputation of being outside of the law. Rumors of bandits and desperados visiting the track were not uncommon.

Walter G. Glasser’s book Guttenberg, N.J: Its Early Days maintains that that the track attracted “underworld elements.” He also claims that multiple larceny, assault, and battery complaints were filed by track-goers.

The clergy takes a stand

Although the track seemed perfectly capable of thriving outside of the influence of law and, conceivably, nature, it was the clergy’s vehement opposition which perhaps led to the demise of “The Gut.”

“As the race tracks in the other parts of the state have been shut up, the gamblers have all come over here, and the rogues are congregated in one place,” said Reverend J. L. Scudder of Jersey City, according to Glasser’s text. “It is not necessary to go to the rogue’s gallery to see the pictures of the criminals and law-breakers. We have only to go up to Guttenberg and we shall see all that we want and the originals.”

In 1893, the track was closed down permanently due to new state legislation, which is commonly believed to have stemmed from the clergy’s outspoken beliefs.

The legacy of the track

The state’s decision ended a short-lived yet unforgettable four years of racing and gambling glory.

After the last race took place, the doors were shut and horse racing in New Jersey came to a halt for nearly half a century.

But upon closing, the site of the track was still able to attract activity. Bicycle, motorcycle, and other race events often would take place. Gypsies were known to use the old stables to shelter their horses and wagons.

In 1919 the lot was subdivided into 1,000 different sections and auctioned off, eventually to flourish into the large residential community that exists there today.

Stephen LaMarca may be reached at slamarca@hudsonreporter.com.