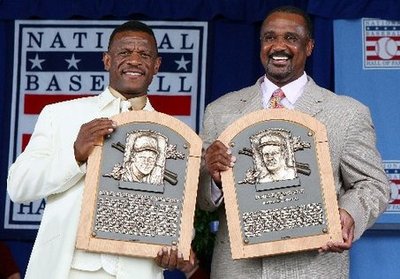

As Rickey Henderson stood at the podium outside the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. last Sunday to accept his induction into the most prestigious of all Halls of Fame in sports, the thoughts flashed back 31 years ago, to when Henderson was just a 19-year-old kid, playing minor league baseball in of all places, Jersey City.

In 1978, Henderson was an up-and-coming prospect for the Oakland Athletics and he was assigned to the A’s Class AA affiliate, called the Jersey Indians, who played their games at the now-razed Roosevelt Stadium. The Society Hill housing development now resides on the spot where Roosevelt Stadium once stood.

Henderson was one of legendary owner Charles O. Finley’s prized prospects back then and the flamboyant and controversial late owner of the A’s wanted to have daily updates about how “my boys” were doing.

So every morning around 11 a.m, a certain 17-year-old would-be senior at St. Peter’s Prep (the team’s owners and officials never realized my true age at the time) would answer the phone call from Finley and give a daily report about Henderson and his other favorites – nicknamed as “Charlie’s Boys,” namely Darrell Woodard, Ray Cosey and Mike Norris.

The quartet of prospects lived together in an unfurnished apartment on Duncan Avenue in Jersey City, right off West Side Avenue. In later days, Henderson would say that it was the worst place he ever lived, but considering he came from the tough streets of Oakland as a kid, his residence in Jersey City couldn’t have been far worse.

Finley also wanted to make sure that his “boys” had proper transportation to and from the ballpark, so the Indians’ jack-of-all-trades (public relations manager, public address announcer, statistician and go-fer) had to make sure to pick up the players on Duncan Avenue before the games and take them home after.

So the four players would pile into the red 1976 AMC Pacer regularly for their rides to and from the ballpark. And it was the Jersey City teenager who was given a little extra in his weekly $200 paycheck to make sure Henderson and his roommates got their ride on time and were kept fairly safe.

Dealing with Rickey Henderson on a daily basis was not an easy chore. I vividly remember one of his first home games that year, when he hit a high pop-up to second base and in frustration, failed to run the fly out. It was a trend that seemed to carry through his big league career.

Well, the second baseman mishandled the pop-up and Henderson should have been standing on second base, but got thrown out at first. The Roosevelt Stadium crowd booed him.

Towards the middle of the season, the Indians were playing the Reading Phillies. Henderson laid down a bunt down the third base line. The third baseman fielded the ball cleanly and proceeded to throw the ball over the first baseman’s head.

Being the dutiful official scorer that I was, I quickly made the call.

“E-5,” I announced, calling it an error on the third baseman. I truly believed that if the throw was made properly, Henderson would have been out, despite his blazing speed.

Henderson was standing on second base when the call was made over the public address system. Needless to say, he was furious, throwing his arms into the air and waving them like a madman.

He was then forced at third base and went back into the dugout.

About a minute later, the phone in the press box rang. I also had to answer the team’s main phone line as the game was going on.

“Jersey Indians,” I answered.

“Jimmy, what the **** do you think you’re doing?” the irate voice said.

“Who’s this?” I said.

“Rickey,” he answered. “Jimmy, that was a hit. Give me a hit right now.”

There was a slight problem. The Indians were taking the field for the next inning.

“Rickey, where are you?” I asked.

“Kennedy’s office,” Henderson said. He was calling from the manager John Kennedy’s office.

“Rickey, we’ll talk about it later, because you have to get back out to centerfield,” I said.

“You better change that call now,” he said as he hung up. He then sprinted from the clubhouse through the dugout and to centerfield before the first pitch of the next inning was thrown.

After the game, I asked both managers, Kennedy and Reading Phillies manager Lee Elia (later known for having an all-time great rant as the manager of the Chicago Cubs) about the play. Elia gave me credit for not being a “homer” and for asking first.

“You’re the best official scorer in the Eastern League,” Elia said to me. It was a great compliment. Henderson got his wish. The error was later changed to a hit.

There was another memorable time in Holyoke, Massachusetts, where Henderson, two other players and me were playing a card game called “Acey Deucey.” And Henderson was clearly cheating, at least it was clear to a kid from Jersey City, not to two farm boys from Oklahoma and Michigan. He was pulling cards from the bottom of the deck to force the others to lose their bets. But the kid from Greenville wasn’t about to be snookered.

“Rickey, pull from the top of the deck, not the bottom,” I said.

It almost led to a huge incident in the hotel lobby, but he changed his dealing ways. Rickey Henderson was already “The Man of Steal” before he earned that moniker.

Henderson also truly believed that he was the only beautiful person alive, that everyone else was ugly. He had degrees of ugliness and called some “mullions,” and others “scullions.” If you were a “scullion,” you were really ugly. I was just a “mullion.”

He also had a habit of barely speaking above a whisper, almost like he was mumbling. I wish I could count how many times I said, “Rickey, what are you saying? I can’t hear a word.” And he would just continue to mumble on, another trait he took through his unbelievable 22-year career.

I remember one day that the Jersey Indians’ general manager Mal Fichman once said in the press box that there wasn’t going to be any of the players on the team that would make it in the big leagues.

“Not even Henderson?” I asked.

“If he does, he’ll be nothing more than a pinch-runner,” Fichman said.

Last Sunday, that would-be pinch runner, who became the greatest leadoff hitter in the history of major league baseball, was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. And I’m proud to say that I knew him when and had the fortune of driving that Hall of Famer all around my hometown when we were both young teenagers.

I got to see Rickey again when he played for the Newark Bears a few years ago. I asked if he remembered me. He didn’t. I had changed a lot since I was 17, having grown almost a foot and gained umpteen hundred pounds.

I let him look at me and said, “Jersey City, I was the PA announcer. I did the stats. I drove you home.”

“Oh, the bubble car,” Henderson said. “I remember the bubble car.”

He recalled the AMC Pacer and not me. Such is life. But he’s now a Hall of Famer and I definitely knew him when…

In other news, Hudson Catholic will announce their new head football coach and athletic director later this week. We’ll have more on that story in next week’s editions… — Jim Hague

Jim Hague can be reached at OGSMAR@aol.com.