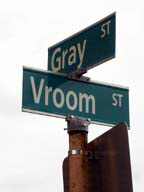

When Eric Deki and James Dorell moved from their Heights apartment to a place south of Journal Square last year, they didn’t know what they were getting themselves into.

Dorell remembers calling his credit card company shortly before the move to tell them about his new address: Vroom Street.

And that’s when the jokes from the customer service representative started.

“She said, ‘You must be really fast on that street,’ or something like that,” he recalled.

“It wasn’t very clever.”

Dorell and Deki now often joke about living on the street with the funny name, but they don’t know its origin.

“Vroom Street?” said Dorell. “Not a clue.”

It turns out, as you might expect, to have nothing to do with speed, cars or a King Crimson album, but like many of the places and streets in this city, it has everything to do with people who helped shape the place we see now. For instance, if you take the train at the Newport/Pavonia PATH station, or are looking for a new car at one of the dealers on Communipaw Avenue, you’re doing so in places named for one individual. One who loved his name, but who never stepped foot in New World soil.

They’re both derivatives of Michael Pauw, an Amsterdam burgermeister (or area magistrate, similar to a mayor) who bought two shoreline properties across from New Amsterdam (now Manhattan), according to “Hudson County: The Left Bank,” a book by Joan Doherty Lovero. The first of these properties, called Hobocan Hackingh by Indians, roughly matches the borders of present-day Hoboken.

The second piece of land he bought consisted of Harsimus and Aressick. That land extends from the Hoboken/Jersey City border down through Bayonne.

“Pauw called this land Pavonia,” writes Lovero, “basing his choice upon the Latin spelling of his own name, pavo, which means ‘peacock.'”

Many are surprised to know that the Communipaw name has nothing to do with Indians.

“It means ‘community of Pauw,'” said Guy Catrillo, chairman of the city’s historic preservation commission and a local amateur historian.

But Pauw never made it from Amsterdam to the New World, and he eventually returned the property to the Dutch West India Company, a trading firm. Before he did that, he hired Cornelius Van Vorst (for whom the Van Vorst Park and Van Vorst Street are named) to help in fur trade and transporting farmers to the new land. And then there’s Michael Paulaz or Paulusen, an agent hired by the Dutch West India Company. His name is now attached to the area known as Aressick, or present day Paulus Hook.

From Tonnele to Tonnelle

Then there’s Tonnele Ave. Or is that Tonnelle Ave? It depends on where you stand in this county. According to county maps, it originates at Kennedy Blvd. in Jersey City, and quickly converges with Routes 1 and 9. Then, at Secaucus Road, it suddenly becomes Tonnelle Avenue until Fairview, where it turns into Broad Avenue.

On the ground, it’s more confusing. A street sign at the Garrison Avenue intersection reads “Tonnele,” while up a few blocks, another reads “Tonnelle.”

Named apparently for landowner John Tonnele, the confusion reached to the newspaper obituaries. The Daily Telegraph mourned John Tonnelle, while the Daily Sentinel and Advertiser announced the passing of John Tonnele.

County spokesman Jeff Jotz told The Reporter a little over a year ago, “It’s just one of the little quirks of Hudson County history that no one has ever seemed to have solved. To be honest, even I don’t know how to spell it.”

Vroom means governor of canals and public education

The Vroom name comes from a family of lawmen. It’s unclear whether they perambulated expeditiously. It turns out that the Vroom family, for which the street is named, is a pretty prominent one in both this city and New Jersey. Peter D. Vroom, a native of Hillsboro Twp., was governor of New Jersey from 1829 to 1836. The family, of Dutch and French-Huguenot descent, moved to New Jersey from New York during the revolutionary war.

Vroom advocated the then-controversial construction of the Delaware and Raritan Canal in New Jersey. He also presided over a government that was the first in the state to distribute money to local townships for public education. The 1829 act was a milestone for the state.

His son, John P. Vroom, an attorney educated at Rutgers, practiced in Jersey City from 1856 to 1863. He was appointed Law Reporter for the Supreme Court in 1862, and began a series of legal reports.