On the evening of April 25, Ron Kraszyk of Bayonne had just come back from dinner with his family and prepared to sit down to watch a New Jersey Devils game on TV when he said he felt odd.

“I never get sick, so I didn’t even have a doctor,” said Kraszyk, who is an account executive with the Hudson Reporter newspaper group. “I’ve never even had a headache, so I never had a reason to go to a doctor.”

Having never been ill in his life, he had nothing to compare this new feeling to. He decided to go to sleep. His bedroom is on the third floor, up 42 stairs from the family room where he watches TV.

“I was never short of breath climbing them,” said Kraszyk. “But this time I felt strange. This came on quick. The only thing I could think was that I had gotten food poisoning. I was very nauseous, and the last time that happened to me was when I drank too much at 17.”

Later, in the early hours of the morning, he got up. He knew what was happening to him wasn’t good. He went into the bathroom and vomited.

He was told later that this was his body’s way of telling him he had a serious problem. He didn’t know it then, but he was on the verge of a massive heart attack. He had no other symptoms, although he had a family history that indicated he was at risk.

“He had no symptoms prior to this,” Dr. Peter Wong, a cardiologist who works at multiple sites in Hudson County, including Hoboken University Medical Center and Bayonne Medical Center. “But this is not unusual. More than 50 percent of people who have heart attacks have no symptoms prior to the attack.”

Fortunately for him, his wife Tish happened to wake up in time to hear him, around 4 a.m.

After he passed out, Tish started to call 911 for an ambulance, but Ron got up and stopped her. He finally agreed that she could take him to Bayonne Medical Center.

Once in the car, he told her not to stop at traffic lights, and she didn’t.

Heart issues

When they got to the emergency room, he collapsed and had a seizure.

“It was surreal at that point,” Tish said. “There must have been 10 people running to him, yelling instructions. Before I knew it, they were rushing him off to the catheterization lab,” Tish said. “It was just like something out of a TV show.”

Someone with a clipboard followed asking questions and getting information as he was wheeled away.

“They were very efficient,” Tish said.

“We have what is called a Code Heart program,” said Richard Butts, executive director of the Cardiac Department. “This is to treat patients who are suffering from a heart attack. What we look for is a set of criteria that shows us that the artery is closed. Upon that recognition of those things, generally there are changes on electrocardiogram that indicate that a heart attack is occurring, then the goal and the best treatment for that is to have the artery open within 90 minutes.”

“Years ago, what we used to give a patient what we called clot-busting medication,” Dr. Wong said. “What we found out is the sooner you can restore blood flow to the heart, the more you minimize the damage to the heart muscle. Clot-busting medicine usually takes several hours to work. So instead, we bring the patient right up to the cath lab where we can do a cauterization and angioplasty.”

Angioplasty is the insertion of a tube through an artery in the leg which can carry a balloon or a variety of other devises to clear the clot from the artery into the heart.

“And very often we will implant a stent that will push the clot aside and allow blood to flow,” he said.

And this can mean a difference between life and death, and even indicate how well a patient recovers later.

“Everybody did what we normally do in this situation. Everybody did well.” – Dr. Peter Wong

_________

Very critical situation

Ron Kraszyk, Dr. Wong said, was at the severe end of the spectrum.

The aorta was 100 percent blocked. The other arteries were 95 to 98 percent blocked.

Ron came into the ER not only suffering from a heart attack, Dr. Wong said, but he also had a condition called carcinogenetic shock. This meant that his heart wasn’t even pumping hard enough to sustain life, to maintain blood pressure.

“What we needed to do first was place a device called an intra-aortic balloon pump just outside the heart and it pumps along with his heart to help his heart during the acute phase of the attack,” Dr. Wong said.

Ron’s heart was also beating irregularly in what is called lethal uremia, and he had complete heart block; the electrical system in the heart became dysfunctional.

“We put in the balloon pump, a temporary pacemaker, and gave him some very specific anti-arrhythmic drugs to stabilize him,” Dr. Wong said. “Then we started working on the blood vessel to his heart. And we found multiple blockages in multiple arteries. We searched out the one artery that was completely blocked which caused the heart attack, opened it up, dissolved the clot, moved in a balloon, and put in a stent to open up that artery. Then we allowed time to let him recover. Within 24 hours, remarkably, we were able to remove his pacemaker and the balloon pump. This meant the heart was able to function in a much better way.”

There was a significant chance Ron wasn’t going to survive.

From Ron’s perspective, the number of people involved gave him confidence.

“They made me feel calmer,” he said, recalling that although several processes were happening at once, one attendant in particular was very collected.

Most of the family had come to the hospital by that time, although one disturbing moment came when Tish was asked by Dr. Wong where their other daughter was. When she said away at college, she was told she might want to bring their daughter back as quickly as possible.

Coded three times

Ron coded three times during the process, and doctors were forced to shock his heart.

For Ron, some of the process was a haze of memory, but he recalled how professional people were and the confidence he felt in them.

“These people were phenomenal,” he said, although he could not remember all of their names.

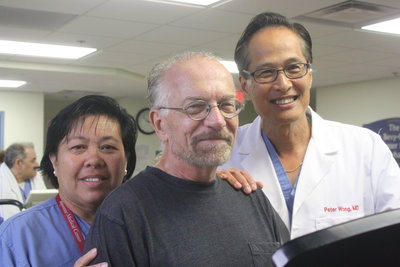

Many of them worked under Helen Uy, manager of the cath lab, who Ron called “amazing.” “They talked to me while I was on the table, asking me how I was and constantly reassured me,” he said.

At one point, they told him that they would need to shock him again, and they told him it wouldn’t hurt, but he would feel like he got kicked in the chest by a horse – which is exactly how it felt, Ron said.

Once in the Cardiac Care Unit, hospital staff never left him in the room alone. Someone was always in there, watching to make certain everything was all right. He said Barbara Reilly and Mark Daniels in particular were “angels without wings.”

“Everybody did what we normally do in this situation, everybody did well,” Dr. Wong said.

“Dr. Wong saved my life,” Ron said.

“Even through Bayonne Medical Center is a community hospital, the kind of care you get here is better than what you would get at any university hospital in the area,” Dr. Wong said. “The only thing Bayonne is missing is the license to do open heart bypass surgery. If that ever changes, Bayonne’s ability to take care of heart patients would be unmatched.”

Ron required quadruple bypass surgery, which had to be performed elsewhere.

Ron’s recovery was remarkable. He started by walking, and eventually wound up working out in the cardiac rehabilitation center at BMC under the careful supervision of Linda Lolli, Ginny Messenger, and Karen Madrid, and along with a new kind of family of others recovering from their own heart issues.

Dr. Wong said even recovery has changed when it comes to heart attacks.

“In the old days, hospitals would keep a patient five or six days up to two weeks after a serious heart attack,” Dr. Wong said. “Now, the idea is to have patients become active and we have them out in 48 to 72 hours.”

“I’m a changed man,” Ron said. “I am very grateful to Dr. Wong and the staff of Bayonne Medical Center for giving me a second chance at life.”