It had been a while since Weehawkenite and trial sketch artist Christine Cornell had traveled out of the tri-state area for work. She preferred local trials so she could care for her 13-year-old daughter, her husband, and her many, many birds, as varied and colorful as the courtroom renderings that were piled high in her studio, amassed over a career spanning several decades.

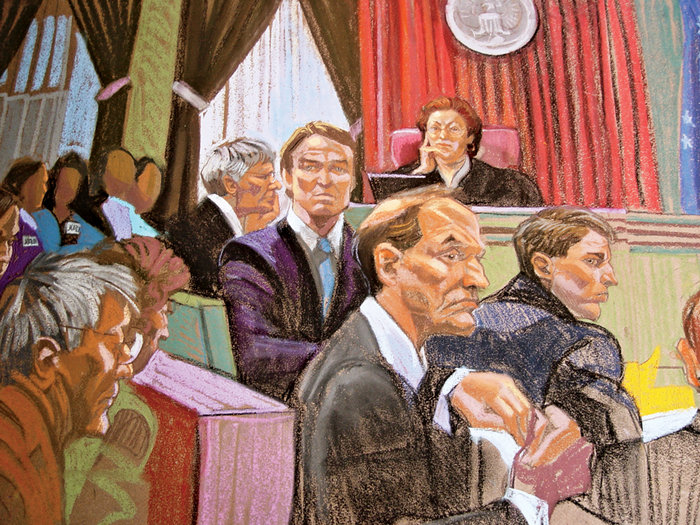

In April, all that changed. She spent six weeks up to her elbows in pastels in the steamy southern town of Greensboro, N.C., before a jury found two-time presidential candidate and former U.S. senator John Edwards not guilty on May 3 on one of six counts of illicit campaign finance-related charges, and found themselves deadlocked on the remaining charges.

“In the end, the jury thought maybe John Edwards knew more than he was willing to admit he knew, but the proof wasn’t there, and it should never have come to trial,” Cornell said. “He did set the cover-up in motion, but bottom line, it wasn’t illegal. It’s not illegal for me to give my fortune away to someone because I think he’s so damned cute.”

“I love the business, I love listening to these stories, I love drawing people and I never ever get tired of it.” – Christine Cornell

____________

He was found not guilty on the third count of the six-part indictment, which alleged that the hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations he received from Mellon to cover his tracks were obtained illegally.

“Bunny once said, ‘I’m just such a pushover for good looks,’” Cornell explained. “She likes being a player on the world stage. As she told John Edwards, ‘We’re going to save the world and have fun doing it.’”

Through the eyes of a sketch artist

Cornell’s journey that led to the internationally renowned trial that touched upon a sex scandal reminiscent of Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky began with an audition for a “Today Show” producer. She got the gig after drawing Edwards from a photo (which she hates, she says, because it doesn’t afford her the same pleasure as drawing from life) and was sent with a reporter and a producer to cover the trial.

She even had her own seat holder, so she could go to lunch and come back to the best vantage point before the courtroom rapidly filled.

Cornell’s unique vantage point extended beyond what it took to best capture her subjects in her renderings, allowing her to speculate on their thoughts, their lives, and their good graces, she explained. Unlike a juror, she was free to wander and to speak with whomever would speak back.

This led Cornell to believe Judge Catherine Eagles may have been biased against Edwards, which then led to a series of interactions with Edwards himself.

“She always voted for the prosecution’s motions and against the defense motions,” Cornell recalled. “There was the day that she wouldn’t allow the transcript of the [Alex Forger, Mellon’s attorney] testimony to be presented to the jury.” Eagles denied the release of the transcript based on its potential bias.

Cornell, incensed by what she felt was unfair, approached Edwards’ attorney and demanded to know why he wasn’t complaining about Eagles’ act, and told him that she had never seen a judge do such a thing in her many years spent in courtrooms.

“I believe the defense was erring on the side of caution with this judge because she was making the rules,” Cornell said, “And they knew she could shut them down if they didn’t try to be very accommodating, conciliatory, and careful.”

Soon after her run-in with the attorney, Edwards was walking by her when he reached out and touched her arm.

“He said, ‘I just wanted to thank you for expressing your support to my team,’” Cornell recalled. “‘I’m grateful for all support because it’s really a tough position to be in. I’m used to being in court.’”

“And I said, ‘Yeah, but not with the gun pointing at you.’”

Close encounters and high profile cases

Ramzi Usef’s wanted poster hanging in Cornell’s studio with “Be mine?” in a thought bubble pasted above his head by her husband indicates that her encounter with Edwards was not her first high-profile interaction.

When Usef was tried in 1995 as the mastermind behind the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, Cornell was there with her pastels when Usef’s attorney approached her with a proposition: a date with his client after the trial.

“The guy was intense,” she said. “Fortunately for me he was never released.”

Cornell has seen (and drawn) it all, from Martha Stewart to John Gotti to the Pizza Connection. The nature of the profession has changed drastically over the years, most notably from contracted to freelance work. And while the demand for sketch artists has diminished considerably over the years, with such a resume, Cornell has no reason to worry over job security.

“I love the business, I love listening to these stories, I love drawing people and I never ever get tired of it,” she said. “It feels like a real privilege to hear them talk about such momentous things and I really enjoy myself there.”

Gennarose Pope may be reached at gpope@hudsonreporter.com