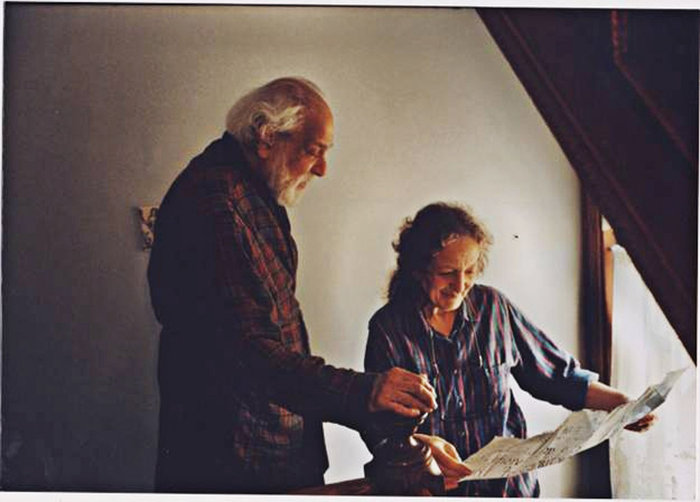

“At first when people asked me to comment on Judy’s life, I wanted to say she was so, so generous,” Pheroze Wadia, Judith Wadia’s husband of 50 years, said as he sifted through boxes of photographs of his late wife’s artwork. “But then I could hear her saying to me, ‘No! I want to be remembered as an artist, not for being generous.’ ”

Judith would have had a point, because her artwork is as prolific as it is beautiful, but Pheroze also has a point, because her public works are equally so.

A memorial was held for Judith, who lost her battle with cancer at the age of 73, at the Weehawken Elks Lodge in December. Mayor Richard Turner posthumously presented Pheroze with a plaque from the town commemorating her artistc legacy and her “quiet good works and unassuming good will [that] improved the life of [Weehawken’s] citizens.”

“If you can make me eat octopus, you can accomplish anything.” – Richard Turner, of Judy Wadia

____________

Literally thousands of people come into physical contact with her work each day as they pass through the many different NJ Transit stations she was commissioned to aesthetically design over the years. In the Edison station, people can sit on her round, brightly-tiled stools as they wait for their trains.

She also led a campaign that contributed to the adoption of the New Jersey Arts Inclusion Act of 1978, which encouraged the commission and installment of numerous works of art in state-financed construction projects.

The community of art

It is difficult to sum up the life work of a woman who had been, as Pheroze mentioned, an artist for 73 years. “There was a humanity and playfulness about her work,” Pheroze said. “Even the most serious thing she did had a certain amount of playfulness about it.”

Judith had been hailed on many accounts for her treatment and combination of colors, which tended to favor the bright side of the spectrum. As Judith was a former physics major, Pheroze explained, she was “always calculating.”

In fact, he continued, one of her main concerns when she received brain radiation was that she’d lose her ability to calculate, which factored heavily into the composition and rhythm of her stained-glass and mosaic pieces.

At the memorial, Pheroze quoted a letter Judith’s close friend Rita Newell sent to her shortly before she died: “When all is said and done, the most that we can hope for is that we have left a legacy of wonderful memories and actions which have enriched our world and the people we have known,” she wrote.

Activism in Weehawken

Judith Wadia’s contributions to Weehawken were extensive. According to friends, admirers, and dissenters alike, she was at every meeting and had her hand in every new project the Planning Board tackled.

She insisted on incorporating green design into every building, implemented rooftop landscaping on all buildings on the waterfront, fought for the preservation of open space, and ensured that the width of the town’s sidewalks would allow for two baby strollers to comfortably pass one another.

She insisted that Turner accompany her on many a sidewalk-measuring jaunt, through rain and wind and all sorts of otherwise unsavory weather.

At Judith’s memorial, Turner told a room full of friends, family, and admirers, “Now you all know Judy – there’s never a ‘no.’ The woman did not understand the word no.”

Turner described one evening when Wadia “dragged” him to PACE University in New York City to a Green Building Design conference. They sat in the seminar for two hours before they discovered it addressed environmentally conscious construction in Arizona – not the Tristate area – and nothing they said had any relevance to Weehawken.

To make it up to Turner, Judith took him out to dinner and made him eat octopus, which he had never tried before.

“Judy,” Turner said, “if you can make me eat octopus, you can accomplish anything.”

“The two had a very vocal but close relationship,” Pheroze said of Judith and Turner. “To say Judy was a strong woman would be a gross understatement.”

To illustrate his sentiment, Pheroze held up a black sunhat that Judith had fitted with bright purple strings of beads where hair would normally hang down. She wore the hat after she lost her hair to chemotherapy, and the beads changed the way people saw her and deflected attention from the obvious.

“This way, people would talk about the beautiful beads instead,” he said.

Judith Wadia’s artwork can be found at www.judithwadia.com.

Gennarose Pope may be reached at gpope@hudsonreporter.com