When Nancy Lomba Dean lost her 10-year-old daughter Marguerite Lomba to cancer last summer, Dean made up made her mind not to see other parents lose their children due to the difficulty in finding a bone marrow match.

“By the time we found a match for Marguerite, it was too late. Her boy was so weak from all the chemotherapy,” said Dean. “I don’t want to see any parent have to worry about that while their child is sick.”

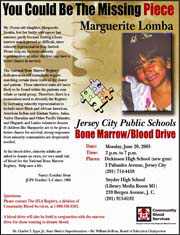

That’s why Lomba, an 18-year teacher in the Jersey City Public School system, is organizing, with the approval of the school system, a bone marrow/blood drive that will take place on June 20 from 2 p.m. to 7 p.m. at Dickinson and Snyder high schools.Finding the missing piece

Bone marrow is the spongy material that fills the cavities of bones and the substance from which many of the blood elements are produced.

Doctors will take a small sample from the breast bone or the pelvis to determine the condition of the marrow.

A bone marrow transplant is the main treatment in some types of cancers such as leukemia or lymphoma. Doctors extract a portion of the patient’s or a donor’s bone marrow, which is then treated and stored. The patient undergoes chemotherapy to kill the cancer cells, but that also kills healthy blood cells. So cleansed marrow is given to the patient through transfusion to replenish the blood cells.

Patients in need of healthy bone marrow usually find a match from a donor who could be an immediate member of their family or a person in their ethnic group.

Lomba was one patient who was in dire need of a life-saving bone marrow transplant. Went home sick

According to Dean, her daughter came home from classes at St. Mary of the Star School in Bayonne in June 2003 and told her mother that she was sick.

First, Dean kept her daughter home and treated her with over-the-counter medicine. But after 10 days, she went to a doctor, worried that her daughter might be more seriously ill. After a blood test was done, Dean was given the terrible news that her daughter was stricken with leukemia.

That led Lomba spending eight months out of the next year at Newark’s Beth Israel Hospital for chemotherapy treatment. She suffered many complications with her condition.

“She would have seizures where she would go into a 20-hour coma. She suffered from diabetes and heart issues,” said Dean over the phone, her voice cracking. “I don’t know how she could have been so happy and full of life after going through all that pain and suffering.”

Dean said her daughter lost 40 pounds during her ordeal, which was prolonged by her daughter’s unique genes – her mother is Scotch-Irish and her father is Cape Verdean. Cape Verde is a nation consisting of several islands off the western coast of Africa that were colonized by the Portuguese in the 15th century. The nation has been independent since 1975.

According to Dean, had her daughter been completely Caucasian, she would have stood a better chance of finding a bone marrow donor match. But her unique genes led to a search for a donor that Dean said was unsuccessful at first, especially when they tried to convince members of her father’s family to donate.

“We tried to encourage members of her father’s family to be tested. I don’t think they understood that you have to do it right away,” said Dean, adding that Marguerite’s brother, Joseph, was not a match.

The process took about a year, with two searches conducted for a match, the second one being successful. But the bone marrow transplant did not succeed, as Marguerite’s body did something that is rarely seen in medical operations such as this – it rejected the bone marrow.

She passed away in July of 2004.

“I still can’t believe that she died. In most cases, people would recover once they receive a transplant, but it didn’t happen for Marguerite,” said Dean. Making sense of it

Dean could have been overwhelmed by sadness in this matter.

But when Dean heard Jersey City Schools Superintendent Charles Epps mention during a speech in the fall of 2004 about a member of the administrative staff receiving a new kidney from a deceased family member, Dean decided to “make sense of Marguerite’s death.”

“I looked around at the people listening to the superintendent speaking, and I thought to myself, ‘many of these people don’t know they could become donors, and that what happened to my daughter could happen to someone in their family,’ ” said Dean.

Dean contacted Epps about the Jersey City School System sponsoring a blood drive. Epps put her in touch with his executive assistant, Dr. Sharon Bartley, and requested that Dean inform the Jersey City School Board about her plans.

After she made a presentation to the board on April 14 of this year, she received approval and has also found an ally in her effort in Board Member Terrence Curran, who is currently pursuing studies in medicine. June 20

Dean said the bone marrow/blood drive on June 20 will be a relatively painless process. “It is a matter of having a sample taken from the pelvis,” she said. “People may be scared, but I look back at Marguerite having to undergo this all the time when she was in the hospital.”

Dean is also planning a fundraiser to benefit the Valerie Fund Children Center at Newark’s Beth Israel Medical Center.

The blood marrow/blood drive will be done by staff from the Bergen Community Regional Blood Center, based in Paramus, for the Human Leukocyte Antigens Registry where donors of blood nationwide are listed.

For more information on the blood drive, contact Dean at (862) 849-3039, Bartley during the day at (201) 915-6227 or Curran in the evenings at (201) 723-2089.