I watched him pull up on his rough road bicycle, its tires popping on the gravel as he stopped near a bench in the Strawberry Fields section of Central Park. He seemed not to care about the crowded world around him, the two dozen television cameras focused on the circular mosaic that decorated the small plaza – a star-like tile artwork that had been installed in this section when the city dedicated it in the early 1980s. No one could see the word "Imagine" in the star’s center because of all of the flowers, candles and messages left by wounded fans.

Despite being less than a week before the traditional gathering here to mark the death of John Lennon in 1980, people crowded the place, crying not over the 20-year-old death of the most cynical Beatle, but over the announcement of George Harrison’s death on Nov. 29.

News of Harrison’s death was released the morning of Nov. 30, bringing many of us to Strawberry Fields – the earliest of us easily ambushed by the expectant media, with camera lenses following each offering as if recording it for posterity.

The bike rider, however, seemed to slip in under the media’s radar; partly because he looked like one of the many messengers who roamed Manhattan’s streets on any busy day. He instantly reminded me of my year as a Manhattan messenger – a part of my life easily recalled by listening to Harrison’s single: "My Sweet Lord," a hit on the radio at the time. The bike rider carried a bundle of white carnations wrapped in plastic, and pulled out a marker, scribbling out some message on the plastic in a language I didn’t understand.

Uncharacteristically of any hardened New Yorker, he left his bike unwatched and eased through the crowd, slipping his flowers onto the makeshift memorial before any camera could catch him.

He might have escaped again, had I not grabbed his arm.

I told him I was a reporter from New Jersey and that I wanted to ask him a few questions. He did not seem totally comfortable, as if I had interrupted a private moment. But he nodded, and we sat on a bench near his bike.

The man’s name was Hamlet Zurita. He was 46 years old, working as an artist in the East Village, part of lower Manhattan. He had bicycled to Central Park to place his flowers on the memorial of a man who had inspired him since he was a young boy.

"I was born in Ecuador," he told me. "When I first tried to learn to read English, I would read the covers of Beatles Albums."

The music on the records needed no real translation, part of that moving international experience the Beatles perfected in their rise during the 1960s. Like the rest of us, Zurita had heard about the death on the news that morning and needed to come to say good bye. The pain in his voice translated easily despite his still thick accent, and after answering a few more questions he rode off the mourn in private.

In search of Michael Marra

I had come to New York via the ferry from Hoboken for two reasons: To mourn Harrison and to track down the particularly illusive Secaucus town clerk, Mike Marra. Although I had called town hall before I left, the clerk’s office did not open until nine. Another contact in town said Marra might be in Manhattan as part of the mourning for Harrison. Marra, a musician and a Beatles fan, had come to Strawberry Fields before during the 1990s, part of the yearly tribute fans made to John Lennon.

Strawberry Fields was the place to which people came whenever there was a concern about one of the Beatles. John Lennon, who lived with his wife Yoko in the nearby Dakota hotel, often wandered in this section of the park during his time living in New York. When he was shot to death on Dec. 8, 1980, a sea of fans filled the whole side of the park, a sea whose tide was turning out again around me for the death of George Harrison slightly over two decades later.

"He certainly left his mark on this world, both musically and spiritually," said mourner Anthony Buccino, a Nutley resident employed near Exchange Place in Jersey City. "The world was a better place – for a while – while he walked it. He will be fondly remembered."

Like a scene from a movie

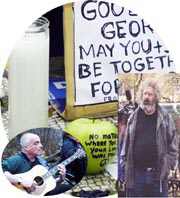

Because the news came so late, many fans had already gone to work before hearing about Harrison’s death, so my early arrival coincided with the early arrival of press from around the world, each of us waiting expectantly for an explosion of emotion. The few fans who arrived early became instant stars, such as Adam Perle, 52, of New York, who had the foresight to bring his guitar and an intimate knowledge of Beatles music, which he played for hours.

Other stars made their dramatic presentations, some of them out of work actors dressed in assortment of colors or garments, a flash back to the Summer of Love when such clothing was fashionable. Their orchestrated movements and their exaggerated expressions became to sole focus of TV crews that had flown in from places like London, Boston, Philadelphia and even LA. Each gesture became a visual for the nightly news, each moan a sound bite.

In the hours that followed, this would change as more and more people left work early to make their pilgrimage here. Yet among the fakers in this remarkable media sideshow, a few people quietly mourned. Like Bob Carpenter, a bear-like man who bore a remarkable resemblance to the late Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead with the same gray hair and gray beard. He stood near the circle, watched the performances, his face full of pain.

When I pulled him aside, he said he hadn’t liked the early Beatles at all. He called himself "a folky," more attached to Bob Dylan during those early days than the Beatles.

"But when they came out with Rubber Soul [a 1966 album] I couldn’t get enough of them," he said. "The song Norwegian Wood really touched me. Later, I came to like the early stuff, but it was Rubber Soul that made me realize how great the Beatles were."

While he mourned deeply the passing of Harrison, he said the former Beatle had left a legacy in music that will be passed on to future generations.

Indeed, in the growing crowd around us, most of the faces were of people not born when the Beatles came to America in 1964 or later when the band broke up in 1970. Many here could not likely even recall the details of John Lennon’s death in 1980.

Local reactions

I could not find Marra’s face in the crowd, but I later located him at work. Like most, he had heard the news late and had too many duties in Town Hall.

"It is definitely a sad event," he said of Harrison’s death. "He was a talented individual. I sometimes think he was underappreciated by general music fans. True Beatles fans understood how much he contributed. He will be missed."

"I was young when they came here," said Marietta Harper of Secaucus, during another interview. "George was always my favorite. He struck me as that deep silent type, you know, like the quiet backbone."

Sharon Griffiths of Jersey City was a Beatles fan since the group came to America in 1964. She attended one of the band’s performances at Shea Stadium in 1965.

"I feared for his safety when he was stabbed two years ago," she said. "I was saddened by his death, but not surprised."

Michele Dupey of Jersey City said she hadn’t made it to Strawberry Fields but had played Harrison’s music, and was a proponent of the Eastern meditations Harrison helped bring to Western culture.

"Like George, my perspective has been changing, understanding that the soul doesn’t change, just the body does," Dupey said. "Your spirit stays with you. Whenever I hear an early Beatles tune, I still get butterflies in my stomach and a sense of childlike wonder and anticipation – just as I felt when I was 11 years old, in 1964."

She called Harrison "a consummate guitarist" and recalled his fascination and study of Andres Segovia, the great Spanish classical guitarist. Dupey attended Harrison’s 1971 "Concert for Bangladesh," which introduced the concept of superstar performances for charity causes.

Mark Lapidos, organizer of the yearly Beatlefest in Secaucus, said the 2002 event is likely to be even more intense than usual.

"It will be a more poignant convention, much like the first one of 1981 was," Lapidos said.

Lapidos has run Beatlefest since 1974, but in 1981, he has dedicated each to the murdered John Lennon. Lennon’s song "Come together," became a kind of theme song to the event, which has drawn more and more fans each year.

The 2002 Beatlefest is slated for March 8 to 10 in the Secaucus Crowne Plaza Hotel. It’s likely to see even more massive numbers and a significant outpouring of affection for Louise Harrison, George’s sister, who has been a yearly speaker there.

Out of the smoke

Most of us present at Strawberry Fields last week had known about Harrison’s impending death. Just as we had followed his career as lead guitarist for the Beatles, we followed his life after the Beatles breakup.

I had a personal relationship with Harrison,s music. When the Beatles broke up in 1970, we passed within blocks of each other. In New York, I skirted through the city as a messenger, a cassette copy of his All Things Must Pass album playing most of the time. Each album, each minor reunion with the other Beatles, inspired in me the hope of an eventual Beatles reunion. Like other fans, we appreciated his solo efforts and his musical association with people like Eric Clapton, Tom Petty, Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, and Jeff Lynne. When he suffered a car accident in New York City in the 1970s, we feared for his death. When John Lennon died and he cried, we cried with him. News of a madman’s attack on Harrison on Dec. 31, 1999 – stabbing him in the lung – sent us all into a panic. We knew he had just recovered from throat cancer. But once there were reports of that cancer spreading, we knew he would die soon, and we prepared ourselves.

Harrison, a lifetime cigarette smoker, died from complications of lung cancer.

The Beatles inadvertently had contributed to forwarding medical research, though. EMI – their record company – made so much money off the Beatles in the 1960s that the company was able to afford the expensive development of the cat scan – one of the chief instruments used in early detection of cancer and other diseases.

Standing in Strawberry Fields last week, I realized how little prepared I was to bid Harrison farewell, as he had helped shape my life since I was a child: each Beatles hit, each film, each expression of art after the breakup was like a chapter in my own family’s notebook. His passing struck me as hard as if a brother or uncle had died, leaving me to understand my own morality.

Fred Gurner, 64, another mourner at Strawberry Fields, was philosophical about the link to one’s own morality.

"That’s what really hits us," Gurner told me, patting my arm as he read my expression. "We’ll miss him, but his passing is a warning to the rest of us."