Directed by Steven Soderbergh; written by Stephen Gaghan; produced by Marshall Herskovitz, Edward Zwick and Laura Bickford; starring Michael Douglas, Don Cheadle, Benicio Del Toro, Dennis Quaid, Catherine Zeta-Jones.

If last year’s predominantly parched cinematic landscape is any barometer, it may be true what they say: when it rains it pours. Up until about two weeks ago, the best movie to have come out in 2000 was Galaxy Quest. And then, with only days before the dawn of the new millennium – and the deadline for Oscar 2000 – production companies finally released the cream of their cinematic crop: the Coen Brothers’ latest epic Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?; Ang Lee’s kung fu extravaganza Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; and Steven Soderberg’s provocative portrait of the Mexican-American drug trade, Traffic.Let’s talk about Traffic.

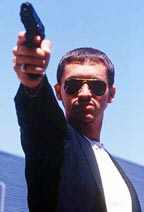

Based on the 1980s British television miniseries Traffik, Traffic braids together three disparate stories. The most publicized plot line is the one that stars Michael Douglas as Robert Lewis, an Ohio Supreme Court justice who has been appointed the nation’s drug czar. “Coincidentally,” the drug czar’s 16-year-old daughter Caroline (Erika Christensen) spends most of her free time smoking, snorting, and free-basing with her wealthy, prep-school companions. While Christensen, cogently portraying a disaffected teenaged drug addict, delivers one of the film’s most poignant performances, the hypocrisy is a little too tidy and ultimately undermines the strength of the narrative.

Out in San Diego, Douglas’ real life wife, Catherine Zeta-Jones, as Helena Ayala, is having some problems of her own. Two undercover drug enforcement agents, Monty Gordon (Don Cheadle) and Ray Castro (Luis Guzman), arrest a middle management drug dealer, Eddie Ruiz (Miguel Ferrer). In return for less jail time, Ruiz names names, including his boss and Zeta-Jones’ on-screen husband, Carlos Ayala (Steven Bauer). Helena is initially horrified – supposedly, she never knew what her husband did for a living. But when her quality of life is threatened, she quickly, and ridiculously, mutates into an evil and duplicitous drug-dealer just like her incarcerated husband.

Down in Mexico, things are even more complicated. A low-level local cop named Javier Rodriguez (Benicio Del Toro), along with his partner Manolo Sanchez (Jacob Vargas), gets roped into working for Mexico’s chief drug official, General Salazar. Filmed in grainy, arid yellows and browns, the scenes in Mexico are visually captivating. Unfortunately, the same can not be said for the plot. With too many characters working for rival cartels, the story becomes a bit murky. In contrast, Del Toro, as the quietly conscientious and honorable good guy, is the most outstanding aspect of the film. He’s the perfect hero, tragic and sullen. And even as he becomes increasingly disillusioned with the system, like all good tragic and sullen cinematic heroes, he continues to do the right thing.

These three disparate stories intermittently overlap and eventually combine to paint a wholly unflattering portrait of America’s war on drugs – wholly unflattering, that is, until the final moments of the film when the portrait is injected with a dash of ersatz optimism, no doubt at the hands of some bottom line Hollywood executive. Complimenting the heady subject matter is Soderbergh’s distinctly raw, unadorned cinematography. And the moody soundtrack, which Soderbergh sparingly intersperses throughout the film, is like the cherry on top of a luscious ice cream sundae.

So, despite some of the film’s fundamental flaws (tidy hypocrisy, murky Mexican plot lines, ersatz optimism and a metamorphosis that would make Kafka turn his head) when compared to other year 2000 options (Autumn in New York, What Women Want, What Lies Beneath, must I go on …) Traffic is a veritable masterpiece. – JoAnne Steglitz